With recent World Athletics Championships, breaking down the science of the javelin

While emerging talent Sachin Yadav impressed with a fourth place finish, back issues prevented Neeraj Chopra from replicating his peak form during the recent World Athletics Championships in Tokyo. What does it take to throw a javelin over long distances?

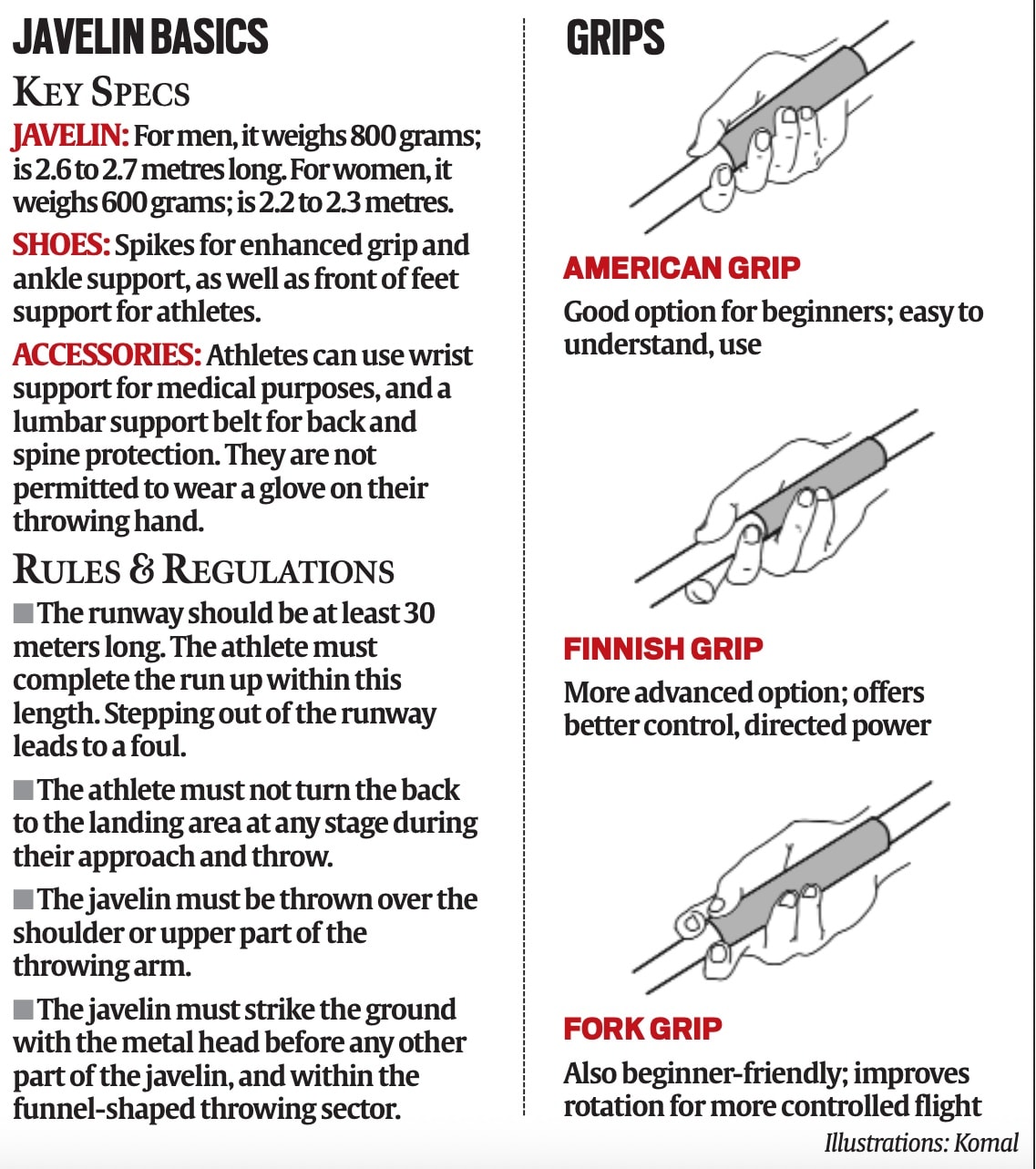

It all begins with the grip. The athlete holds a synthetic/cotton cord wrapped around the javelin at the centre of gravity. There are three popular grips.

It all begins with the grip. The athlete holds a synthetic/cotton cord wrapped around the javelin at the centre of gravity. There are three popular grips.

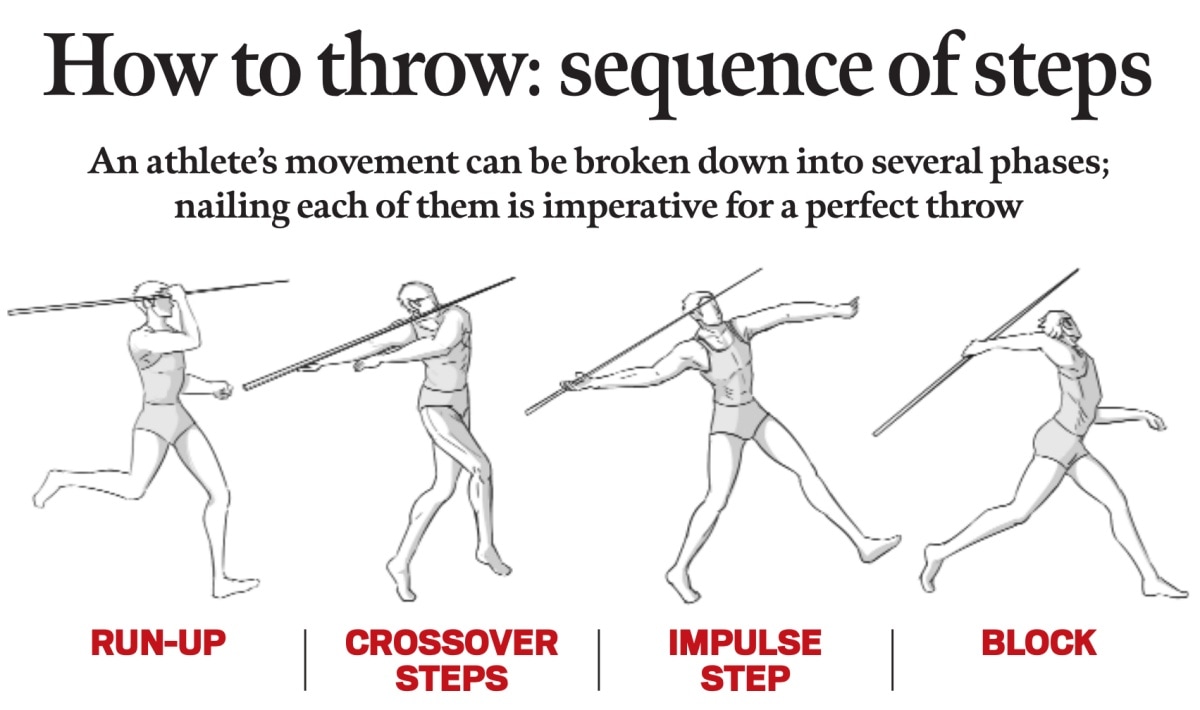

Javelin throw is one of the most technically challenging track and field disciplines. A javelin thrower’s movement can be broken down into several phases and every tiny action matters. Athletes seek to optimise their actions during each phase to hurl the javelin further into the horizon.

Here’s a breakdown.

The grip

It all begins with the grip. The athlete holds a synthetic/cotton cord wrapped around the javelin at the centre of gravity. There are three popular grips.

Javelin grips

Javelin grips

American grip: The thumb (inner side, closer to the throwing shoulder) and the index finger (outer side) are placed at the top of the cord while the remaining three fingers are placed around it. The index finger is key. “Make sure the pointing (index) finger is tied to the grip (cord) to transfer most of the energy,” 2016 Olympic champion Thomas Röhler explains in an YouTube video titled ‘How to throw the javelin’.

Finnish grip: Finland was once a powerhouse in javelin throw: till date, it has won 22 of the 81 medals in men’s javelin at the Olympic Games. The Finns developed a grip in which the index finger is placed under the javelin, just above the cord. India’s Neeraj Chopra, who won the gold medal in Tokyo 2020 (held in 2021) and a silver in Paris 2024, usually opts for this grip.

V-grip or fork grip: The top of the cord is gripped by the index and the middle finger, while the ring finger and the little finger go around the cord. “The reason people with elbow problems use it is because you always have the javelin on top of (above) the elbow,” Röhler said.

Run-up & crossover

The run-up is where a javelin thrower gets into a running rhythm. The number of steps varies from athlete to athlete: Germany’s Julian Weber takes 10 to 12 steps, while Chopra takes about 15. The idea is to gain momentum which can then be transferred into the throw.

How to throw a javelin

How to throw a javelin

During the run-up, the javelin is held above the shoulder level while the athlete runs in a straight line (before entering the crossover phase).

Rhythm is key, 2010 Commonwealth Games bronze medalist Kashinath Naik told The Indian Express. “The run up steps have to be in good rhythm. And after that when the crossover steps begin, the speed needs to increase steadily, along with maintaining rhythm,” Naik said.

The crossover is essentially the movement with which the javelin thrower transitions from running straight to sideways. Entering the crossover, the thrower extends her throwing arm as far back as possible, placing the javelin in a launch position. The arm, however, must be kept relaxed.

The biggest challenge with the crossover is maintaining upper-body stability: this is because the motion requires an athlete to plant the right leg in front and across the left without transferring the weight forward prematurely.

Most athletes take three or four cross-steps (counting only the planting of the right leg); overstriding can kill the momentum gained.

The impulse stride

At the end of the crossover, the body weight is on the balls of the right foot (for right-handed throwers) as the left foot extends forward. The thrower then starts rotating on the balls of the right foot after it is first placed at an ideal angle of 45 degrees towards the throwing direction.

The athlete leans back before the power from the right leg is transferred into the throw via the hips to the upper body. This is known as the ‘power position’.

“The right leg should be angled between 20 to 45 degrees. The trunk of the body should also be leaning backwards to allow for the power to be generated and rotation of the body in the direction of the throw and to enable speedy forward movement,” Naik, who had coached Chopra in his early years, said.

A javelin thrower’s legs are all-important.

“The throw is built up from the legs. Legs, starting with the ankle and the toes, must be strong. All little joints are involved in building up the throwing movement from the bottom,” Klaus Bartonietz, Chopra’s coach during the Paris Olympics, said.

“I like a quote from (martial artist) Bruce Lee. He said ‘take the power from the ground through your legs, the waist and into the arm’,” Bartonietz said.

Block, release angle

The blocking leg, the left one for a right-handed thrower, is planted like that of a fast bowler — without bending the knee.

“The left leg during the block should land in the same line as the heel of the right leg (when the ball of the right foot was planted for the impulse stride),” Naik said.

The block allows all the power to be transferred into the throw. And in the process, it puts extreme pressure on the body. “We have one tonne of weight, which is like a small car, on the block foot… So it’s really tough,” Röhler had said in July.

Julius Yego, the 2015 World Champion, compared the blocking phase to a handbrake being pulled when a car stops. “Because you need to stop. It is like, sometimes you are going 100 kmph in a car and you have to use the emergency brake,” Yego had told The Indian Express in July.

The angle of the release of the javelin should ideally be between 32 and 40 degrees, depending on the conditions on the day of the competition, to maximise the distance.

Although high school physics textbooks say that for achieving maximum range, a projectile should be launched at a 45-degree angle, this is only true for a situation where the launch occurs from the same height as the target.

In the case of a javelin, the athlete’s height means that the javelin is launched from roughly 2 metres above the ground.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05