Ratan Tata’s Indica: How he shaped India’s first indigenous car

As one of India’s greatest industrialists passes away, a look at what might be one of his greatest achievements — creating the first truly indigenous Indian family car.

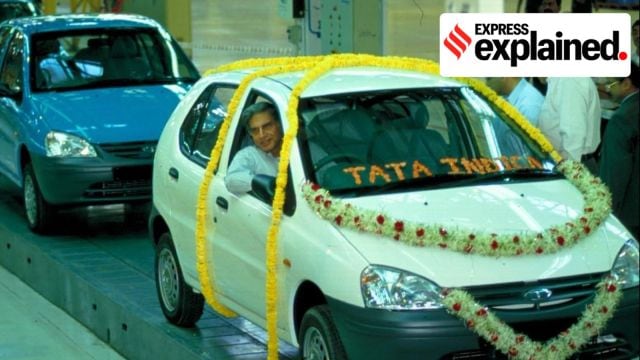

Ratan Tata at the Indica manufacturing facility. (File)

Ratan Tata at the Indica manufacturing facility. (File)The Suzuki suffix meant that Maruti was never truly an Indian car. The Ambassador — although assembled in India — was essentially an Indian-assembled version of the British Morris Oxford. India did not have a truly indigenous car. Until Indica.

Unveiled in 1998 at the Auto Expo in Pragati Maidan, Tata’s first foray into passenger vehicles was game-changing. And behind it was the vision of one man: Ratan Tata.

Quintessential family car

Ratan’s predecessor, JRD Tata, had dreamt of launching a fully indigenous family car. But the government’s policies at the time did not allow him to proceed. The idea of Indica came up only after 1991 — when JRD stepped down and named Ratan as Tata Sons chairman, and India’s economy underwent structural reforms.

Ratan Tata made his plans public in 1993 at an exhibition of automobile component manufacturers. Summing up his vision, he would famously say in an interview with the magazine Bussinessworld: “It would have the size of the Maruti Zen, the internal dimensions of an Ambassador and come at the price of a Maruti 800 with the running cost of a diesel”.

Moreover, given the state of Indian roads, the car would have to be tough. For foreign markets, it had to be aesthetic and fulfil necessary safety criteria. What Ratan Tata was proposing was a something that had never been done before.

Designing an indigenous car

Developing this car would not be easy — or cheap. To begin with, Ratan Tata put in place a new engineering team to come up with the car’s design.

“He picked the best design engineers and put them on the job at TELCO’s Engineering Research Centre,” journalist Girish Kuber wrote in his book The Tatas: How a Family Built a Business and a Nation (2019).

“Computer Aided Design or CAD had not become popular, but Ratan, knowing its potential, invested in a facility, spending Rs 120 crore. It had 225 computers and nearly 350 engineers working to create a world-class design,” Kuber wrote.

And after Indian engineers completed their work, he sent the design to a famous automotive design institute in Turin, Italy. He also got French engineers to help with the car’s engine. His response to those who criticised his decision to seek help from abroad: “There [is] nothing wrong in learning from the world’s best”. A prototype was finally readied in Turin, and then shipped to Pune.

Challenge of manufacturing

Mass manufacturing the car would be an even bigger challenge. “Most of the vendors and the assembly line workers were used to assembling trucks, in the case of which precision was not tested to the extent it was in car manufacturing,” Kuber wrote.

Ratan Tata personally worked with nearly 300 small-scale manufacturers in and around Pune, as he wanted to ensure that nearly 98 per cent of the parts were indigenously manufactured. This alone generated 12,000 new jobs, Kuber wrote.

And then Ratan set up a completely independent assembly line over a space of 6 acres in the TELCO (later renamed Tata Motors) factory in Pune, the scale of which convinced people that he was “thinking big”. An unused Nissan manufacturing plant from Australia was disassembled and shipped to the Pune factory, which was developed keeping in mind the convenience of his workers.

“In one of his visits, he realised that the worker would have to bend twice to assemble a particular part. If the plant were to manufacture 300 cars a day, it meant bending 600 times. This was unacceptable to him. ‘Get a robot here,’ he said. ‘We cannot allow such back-breaking work to be done by our people’,” Kuber wrote.

Ratan Tata also provided workers inside the factory with bicycles, so that they could traverse up and down the facility with ease. Once the assembly line picked up by mid-1999, the factory was churning out a car every 56 seconds.

In the leadup to Indica’s market release in 1999, a successful marketing campaign — the slogan “More car per car” became hugely popular — meant that over 1.25 lakh initial orders had already been placed.

Setbacks and rise of V2

The initially launched model, however, was plagued with manufacturing problems and a host of other issues. The naysayers soon stepped in. Financial dailies lambasted Tata for entering the car manufacturing business, editorials took Ratan to task for indulging in this “vanity project”. A lot of heat was focussed on the “indigenisation” of Indica, something that left Ratan Tata very upset.

Calling a meeting of senior executives of Tata Motors, Ratan took candid (often damning) feedback, and began working on a solution. In the short term, it was decided that the company would hold countrywide customer camps and replace all defective parts, free of cost. A whopping Rs 500 crore was spent on this, as Ratan Tata announced: “We shall do whatever it takes to make Indica trouble-free and make you a satisfied customer.”

Simultaneously, engineers went to work on ironing out the kinks in the manufacturing process and coming up with a better Indica — Indica V2. This went on to become one of the most successful cars in Indian history.

As an article on Autocar India stated: “Compared to its global rivals, the homegrown Indica was still crude, rough around the edges and continued to have few niggling problems but these faults were overlooked by the sheer value proposition it offered. Cheap to buy, cheap to run (it was the only diesel in its class for years) and cheap to repair, the big and spacious Indica truly lived up to its ‘More Car per Car’ marketing tag.”

And behind this game-changer was the belief a certain Ratan Tata had in himself, and the belief he instilled in Tata Motors engineers.