The Tramp Who Lives in Jungfrau

Charlie Chaplin’s home in Switzerland remains a very popular draw for fans across the world.

A scene from The Great Dictator. (Source: Charukesi Ramadurai)

A scene from The Great Dictator. (Source: Charukesi Ramadurai)

Growing up in the days of black-and-white, single-channel television meant, among other things, that one of my favourite childhood icons was a man with a funny moustache and a funnier walk. His coat never fit him properly, his hat kept falling off, and his walking stick was a weapon of mass destruction against anyone who wished him harm. He never seemed very aware of the chaos he caused around him — fading out of the screen instead, shrugging his shoulders and smiling shyly. Suffice to say, I could never have enough of Charlie Chaplin.

But it was not until I was much older that I became aware of the subtext of most of Chaplin’s work: the indignity of poverty and the pathos of longing. Over time, I lost touch with Chaplin’s work, until a recent visit to Switzerland took me to his home along the shores of Lake Geneva. This was to be his sanctuary after he was denied a visa to return to America in 1952 — his closing speech in The Great Dictator had led to suspicions about his communist sympathies. And so it was, that in far away Switzerland, Chaplin set up his home with his wife Oona, and their eight children. Chaplin lived there for the last 25 years of his life. Here, Chaplin continued to make movies, compose music, travel the world — and long for the adulation of Hollywood.

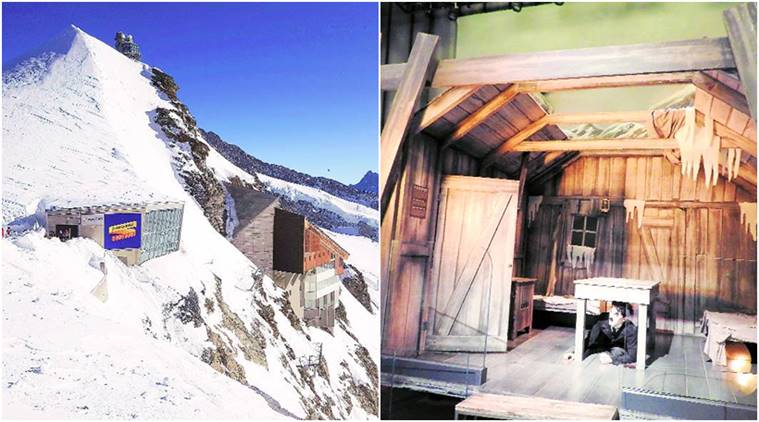

(L-R) The snow-covered peaks of Jungfrau; and the famous snowstorm scene from The Gold Rush, recreated in the studio. (Source: Charukesi Ramadurai)

(L-R) The snow-covered peaks of Jungfrau; and the famous snowstorm scene from The Gold Rush, recreated in the studio. (Source: Charukesi Ramadurai)

Walking through his home, the Manoir de Ban — converted recently into a museum devoted to Chaplin’s life and work — I got a glimpse of the man behind the comic genius. The property stretches over 35 acres, and a part of it — his private residence — has been preserved just as it was during his lifetime, with rare family photographs showcasing him as a husband and father. Another part of the property is a studio which offers visitors a walkthrough experience of his filmography, complete with interactive exhibits. I walked tentatively on the tilting mountain cabin from The Gold Rush and marvelled at how he pulled that stunt off nearly a century ago.

My visit happened to coincide with Chaplin’s 40th death anniversary (on Christmas day). To mark the occasion, Chaplin’s World (the Manoir de Ban, now converted into the Chaplin’s World museum) along with Jungfrau Railways, had commissioned British sculptor John Doubleday to create an ice sculpture of Chaplin. It was to be inaugurated at the Ice Palace, a small museum atop the Jungfrau summit — one of the main summits of the Bernese Alps, in western Switzerland. And so, from Vevey, a town by Lake Geneva where I was staying, I headed towards the hills.

My base for Jungfrau was Interlaken, a couple of hours by road from Vevey, and the main gateway to the Bernese Alps — a pretty Swiss town made famous in a thousand Bollywood films by the redoubtable Yash Chopra; they even have a statue of the director in a park! From my window at the Victoria Jungfrau Grand Hotel and Spa in Interlaken, Jungfrau and the neighbouring peaks of Eiger and Mönch winked alluringly at me, as the sun set in the distance.The next morning, I found Interlaken covered in a blanket of fresh snow as we left for Jungfrau, changing three trains in less than two hours. After our first stretch up to Grindelwald, we climbed further up to Kleine Scheidegg, a mountain pass.

For most of the way, all I saw around me was a thick cover of white, with tiny wooden homes popping up occasionally, wisps of smoke trailing out of their chimneys. As we went higher, a few skiers appeared in the distance, clomping their way up or whizzing down through the snow. A couple of startled chamois deer made a rare appearance right by the tracks, before bolting off.

When we finally arrived at Jungfrau — popularly known as the Top of Europe, at an altitude of 11,332 feet — the temperature was minus 12 degrees. The sharp sun and the snow left me sweating and shivering by turns, depending on where I stood, and I felt thankful for the sunscreen and sunglasses (and the several layers of thermal wear underneath my jacket). I waited for the novelty of gazing at snow-clad peaks to wear off but that did not quite happen; everywhere around me, it seemed stunning.

Soon enough, we made our way to the Ice Palace — where the tunnels and hallways are made entirely of glassy ice with niches containing sculptures of birds and animals on display through the year. I headed to the area where Doubleday was waiting for me, along with representatives from the Chaplin Museum and the Jungfrau Railways — for the formal inauguration of the statue.

The ice sculpture depicts Chaplin in perhaps his most famous role, the lovable Tramp, along with the Kid. Doubleday shivered as he posed for photographs, saying in jest, “never again ice” as he recalled the eight months he spent chiselling this work of art. “I think of this (figure) as quintessential Chaplin, somewhat lonely and fragile, but also full of the fighting spirit,” he said when I caught up with him for a quick chat.

On the way back to Interlaken, I wondered why Chaplin still remains so popular and relevant. Perhaps, the clue lies somewhere in that very speech that riled the American authorities: “Let us fight to free the world — to do away with national barriers — to do away with greed, with hate and intolerance.”

The writer is a Bangalore-based freelance journalist and photographer.

- 01

- 02

- 03