Stay updated with the latest - Click here to follow us on Instagram

Near Delhi, a manual scavenger’s wish: ‘hope my children escape trap’

One year of Swachh bharat abhiyan, a tale of two toilet projects.

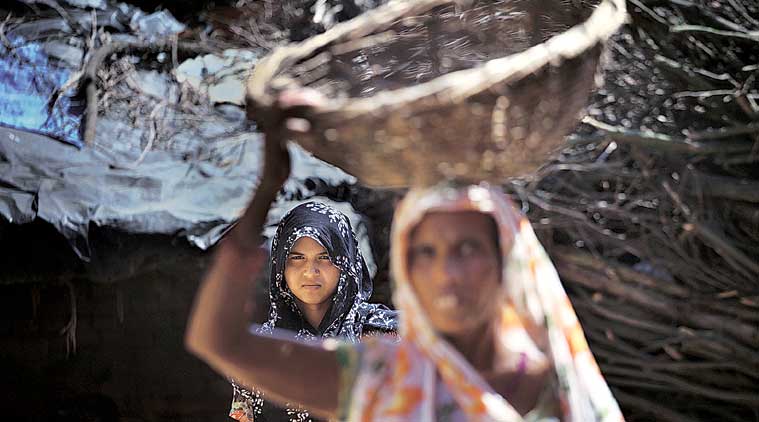

Maya and her daughter-in-law Preeti work as manual scavangers in Nityanandpur village in Meerut district of Uttar Pradesh. (Source: Express photo by Oinam Anand)

Maya and her daughter-in-law Preeti work as manual scavangers in Nityanandpur village in Meerut district of Uttar Pradesh. (Source: Express photo by Oinam Anand)

This Gandhi Jayanti, on the first anniversary of Swachh Bharat Abhiyan, it will be just another day at work for Meena in Nityanandpur, barely 100 km from the national capital.

Beginning 7 am, she will visit 25 homes in her village in Meerut district where she will scoop human excreta from open-pit latrines, using only a tin sheet, and pile them on to a cane basket. After every three homes, she will trudge to the woods nearby to empty the full basket. For her labour, Meena will be get a 6-kg sack of wheat from each house every year, in addition to some rotis once every few days.

[related-post]

Thursday was a particularly tiring day for her. “I have been suffering from dengue for the last fortnight so I couldn’t go to work for three days. Today, the workload was too much and stench was particularly unbearable,” said Meena, in her 40s, as she sat down to clean herself.

Meena’s is one of the four Balmiki families living along the periphery of Nityanandpur, whose women have known no other work than lifting night soil. The daughters start as young as ten and continue to till they move to another village — meanwhile, the daughters-in-laws who come in take over.

Each woman cleans 20 to 25 dry latrines, mostly in the homes of the poorer Muslim community. The Chamars, Malis and Gujjars are sightly more well-off and have toilets that flush out into septic tanks. The Balmiki men, who on most days do odd jobs, lower themselves into these tanks once every 15 days to scrub them clean. “We are paid Rs 200 each time we empty the tank and carry its contents to the woods in a handcart,” said Meena’s 25-year-old nephew Pramod.

Unlike those from other communities, these four families have no access to toilets and relieve themselves in the woods. Meena and the other women have to wait for their turn until after dark.

Manual scavenging has been outlawed in India since 1993, and its eradication is one of the key aspects of the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan, a flagship initiative of the Government. And yet, as per the Houselisting and Housing Census, 2011, there are 7.94 lakh dry latrines in the country from which night soil is removed by humans.

In 2013, the legislation was amended to provide for the rehabilitation of such workers. Since there’s presently no definitive data of the number of manual scavengers in the country, the process of rehabilitation was to start with a survey, to be completed by end of 2014.

As per figures, Meena’s state of Uttar Pradesh accounts for 80 per cent of the 12,226 manual scavengers identified in the country till date. But merely 12 of the 35 states and union territories have bothered to submit such data — big states such has Maharashtra, Gujarat, Jammu & Kashmir, Tamil Nadu, Arunachal Pradesh, Jharkhand and even Delhi have nothing to show.

Moreover, the numbers include only those cleaning open pit latrines. The last available data, compiled from 24 states in 2007, had pegged their numbers at 3.42 lakh.

Safai Karamchari Andolan convener Bezwada Wilson, who is part of the Central monitoring committee for implementing the new law, said, “The number of men employed by the Railways to handle the excreta, or those cleaning sewer lines and septic tanks, find no mention even in official records even though the Act recognise them too as manual scavengers.”

In the house next to Meena’s is the village’s latest entrant to the job. Eighteen-year-old Preeti, who was married into the house a year ago and is now pregnant, has joined her mother-in-law Maya in the daily routine. “I had eight children and I did this work all throughout the nine months of pregnancy and went back to it within 15 days of my children being born. Preeti has been doing this job in her mother’s village since she was ten years old. And yet the first time I took her to work with me, she threw up all over. Now she is getting used to it,” said Maya.

While Preeti herself was forced to drop out of school, she has a dream for her unborn child, a dream shared by the other three Balmiki families none of whom are allowed inside the homes of the people whose latrines they clean. “I want to educate my child. All of us are sending our children to the government school in the hope that at least they will escape this trap forever,” said Preeti.