Stay updated with the latest - Click here to follow us on Instagram

1984 anti-Sikh riots: ‘The bodies were here, everywhere… in the dark, all I could see were fires’

Block 32, Trilokpuri. This east Delhi neighbourhood was Ground Zero of the 1984 carnage in the Capital where 350 Sikh residents were killed in 30 hours. The first reporters to reach the spot were Joseph Maliakan and his colleagues at The Indian Express.

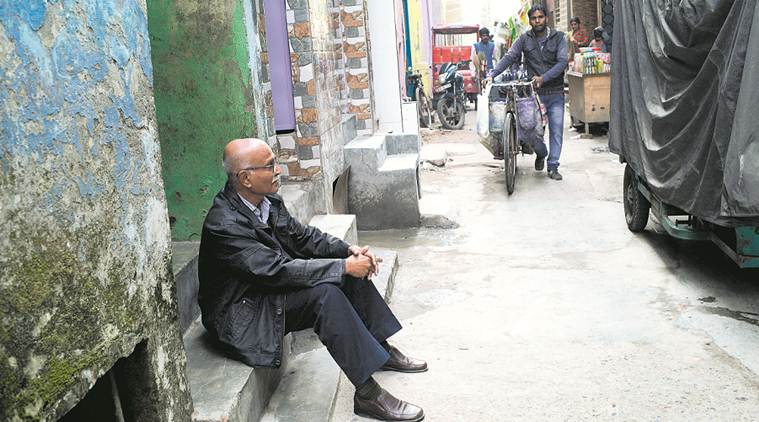

In the days since the December 17 verdict of the Delhi High Court sentencing Sajjan Kumar, who has since resigned from the Congress. (Express: Neeraj Priyadarshi)

In the days since the December 17 verdict of the Delhi High Court sentencing Sajjan Kumar, who has since resigned from the Congress. (Express: Neeraj Priyadarshi)

“Jacob?”

“No. Joseph.”

“Aji haan, Joseph. Kaise ho tussi (Oh yes, Joseph. How are you)?,” says a beaming Mohan Singh, stretching out his hand to pull Joseph Maliakan into a hug. The two men have met after 10 years in West Delhi’s ‘Widows’ Colony’ in Tilak Vihar, but theirs is a relationship that goes back 34 years. Thirty four years to the day when Delhi was ripped apart in one of the worst riots witnessed in post-Independence India.

In a pre-Internet, pre-cellphone era, it was Mohan Singh’s tip-off that helped Maliakan, then a 36-year-old journalist with The Indian Express, and his colleagues uncover mass killings in East Delhi’s Trilokpuri, one of the worst affected areas during the 1984 anti-Sikh carnage. The mindless bloodshed that claimed over 2,700 Sikh lives in the Capital alone, the frightening memories in its aftermath and an investigation spread over three decades and 11 commissions helped forge an unlikely friendship between a Sikh and a Malayali Christian.

“If it wasn’t for him, we would have never known the extent of the murders in Trilokpuri, which saw the maximum number of killings of Sikhs in Delhi at the time,” says Maliakan, now 70.

As the two men settle down for tea at Mohan Singh’s two-room house in Tilak Vihar, which he shares with his two sons, both drivers, daughters-in-law and grandchildren, Singh, now 60, recalls how his two brothers, then in their 20s, had been burnt to death.

Mohan Singh, an ‘old source’ for reporters at the Express, visited the office often. His tip-off helped Maliakan and his colleagues uncover the Trilokpuri killings. (Express Photo: Neeraj Priyadarshi)

Mohan Singh, an ‘old source’ for reporters at the Express, visited the office often. His tip-off helped Maliakan and his colleagues uncover the Trilokpuri killings. (Express Photo: Neeraj Priyadarshi)

“On the evening of November 1, 1984, police in Trilokpuri disarmed all the Sikhs and told us to go inside our homes. They said they would protect us. That night, there was no electricity, it was pitch dark. Most people were preparing to retire for the day, some of us had gone to a naala nearby to relieve ourselves, when a mob came charging. That saved me and a few others. All the men in the homes were killed. The attackers were drunk, they raped our women and burnt our children. My brothers are gone,” says Singh, breaks down. Maliakan, sitting cross-legged on the bed with his old friend, consoles him. The two men continue holding hands.

In the days since the December 17 verdict of the Delhi High Court sentencing Sajjan Kumar, who has since resigned from the Congress, to life imprisonment in a case where five members of a Sikh family were killed in the Capital’s Delhi Cantonment area, the sights, sound and smell of the massacre — Maliakan’s “worst assignment” — have come rushing back. As he revisited the chaotic streets of Trilokpuri and Tilak Vihar with The Sunday Express, the stories flowed.

***********

It was November 2, 1984, 11 am. Mohan Singh, a Sikh auto driver and an “old source” for reporters at The Indian Express, arrived at the newspaper’s office on Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg. “He was bleeding. He was not wearing his turban. He told me Sikhs are being butchered in Trilokpuri and pleaded with us to do something. We decided to go,” says Maliakan, his eyes wide under his glasses.

Recalling the dread and panic that filled him as he fled the rioters in Trilokpuri that day, Mohan Singh says, “I first went to Kalyanpuri police station, but they said I was a Sardar and that they couldn’t help me. That is when I threw my turban and chopped my hair ‘jaise taise’ (roughly)”. I then borrowed a cycle from a relative and went to the Delhi Police Headquarters near ITO. But there too I couldn’t get past the gate.”

By then, it had been 48 hours since the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, on October 31, 1984, and the Capital had plunged into chaos. Maliakan recalls how reporters had fanned out across the Capital but got little by way of numbers to understand the scale of the killings. He himself had spent hours on the field with little success.

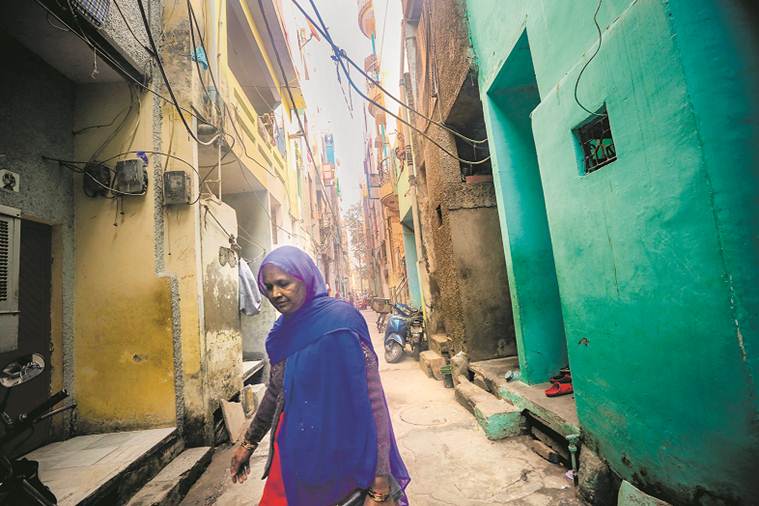

Kanwaljit Singh Sandhu breaks down as he talks about his brothers, 12 and 18 then, who were burnt to death in the riots. (Express Photo: Neeraj Priyadarshi)

Kanwaljit Singh Sandhu breaks down as he talks about his brothers, 12 and 18 then, who were burnt to death in the riots. (Express Photo: Neeraj Priyadarshi)

“Police did not give us anything. They denied the killings. We had heard about and seen several attacks, but we needed official numbers. When I told one of the officers at AIIMS (All India Institute of Medical Science) that Sardars were being beaten up on the streets and vehicles being burnt, he said, ‘I can only take care of Mrs Gandhi’,” recounts Maliakan.

Then, with a shaken Mohan Singh alerting them about the deaths in Trilokpuri, Maliakan and his colleague Rahul Bedi, along with Alok Tomar of the Jansatta, decided to go to the East Delhi colony. They thought they would take Mohan Singh along and even got him a sharper haircut at a barber’s behind the Express office, but later decided against it. “Taking him along would have been too risky,” says Maliakan.

For the next three days, Mohan Singh would stay at the newspaper office before leaving for his village in Rajasthan.

Around 2.30 pm on November 2, 1984, the reporters managed to reach Block 28 of Trilokpuri. “We found our way through one of the lanes at the back of the colony. Two people had been killed there. A group of around 50 men armed with swords and rods charged at our vehicle. Rahul Bedi pointed to his throat and said, ‘We are finished’,” recalls Maliakan. “But fortunately, the leader of the mob just asked us to go back. They pelted stones at our Ambassador though.”

Later in the evening, after a trip to the Delhi Police headquarters, says Maliakan, the team decided to make another attempt to enter Trilokpuri. This time they were successful.

On their way from Lakshmi Nagar to Trilokpuri, Maliakan witnessed another “horrible sight”. “We were on an overbridge and on the railway track running underneath, a local train had halted. Bodies of Sikh men hung out from the coaches. It was a nauseating sight,” he says.

That day, around 6 pm, the reporters managed to enter Trilokpuri. A crush of women and children — “there were around 50 of them” — charged out of homes in a narrow, dark lane opposite Block 32 in Trilokpuri. One of them, “Inder Kaur”, and her child grabbed his arm and begged, “Save us”.

Maliakan stood there, frozen.

The air reeked of soot and burnt tyres, and was now shrill with the wails of the widows. The children were quiet, still in shock after the “30-hour carnage”. Some were running high fever. The women and children, Maliakan recalls, had no food and water for hours. “I managed to spot a handpump and brought some water for them. I felt helpless,” says Maliakan, now walking with his hands in his pockets, eyes fixed on the road below.

Pictures of victims at local gurdwara. (Express Photo: Neeraj Priyadarshi)

Pictures of victims at local gurdwara. (Express Photo: Neeraj Priyadarshi)

On these very lanes then, Maliakan and Rahul Bedi had found themselves walking in the dark, tripping over charred bodies of Sikh men, some still bleeding, others stacked in a pile, burning. “The bodies were everywhere. In Block 32, bodies were being burnt to destroy evidence. In the dark, all I could see were fires. The stench of flesh…” he says.

Later in the night, when, on the reporters’s insistence, a police van arrived to rescue the survivors, there was a stampede. “People were falling over one another to get into the vehicle, children were getting crushed in the crowd.”

Thirty four years later, on a Wednesday morning, as Maliakan arrives in Trilokpuri, it is business as usual — men working at automobile repair shops or hawking their wares and women busy with household chores. “It’s overwhelming,” says Maliakan as he makes his way into the colony.

“Those days, there was nothing in Trilokpuri. Dalit Labana Sikhs were shifted here from slums in Shahdara, about 15 km away, as part of a clear-up during the Emergency,” says Maliakan, walking past carts selling kitchen utensils, toys, bright spangled woollens, snacks. “Back then, most men here made a living selling charpoys and sharpening knives.”

The locality now has a mix of Hindus and Muslims. Only 10-12 Sikh families remain, but none in Block 32, the epicentre of the carnage in Trilokpuri.

Standing outside one of the main roads leading to the neighbourhood, Maliakan recalls how it had been blocked with eucalyptus trunks during the riots. Standing at the spot that’s now flanked by small shops and pointing to eucalyptus trees on the left, he says, “See these trees? It is easy to cut them.”

***********

In the years since the 1984 riots, Trilokpuri, a sprawling 90-acre colony divided into 37 blocks, has been in the news, mostly for violence. This year alone, there have been two incidents of communal violence — in February, tension simmered after two groups clashed over the death of a Dalit man and in July, clashes erupted after an argument during a cricket match turned ugly.

But it is the shadow of the 1984 violence that the colony has found hard to shed.

Twenty-seven-year-old Sohan Singh, who lives on the premises of the gurdwara near Block 32, talks about the stories he has heard from his grandfather. “The mob burnt down this gurdwara. Several men died. The granthi (priest) kept reading the Guru Granth Sahib as the place was set ablaze. He was burnt too, still reading,” says Sohan, who has a “private job”.

Today, much like his days as a reporter, Maliakan pulls out a small writing pad and begins to scribble down notes, adjusting his glasses and often interrupting to ask questions, nodding and smiling.

“Back then, I couldn’t take out my notepad, I would have been thrown out if I did. But the images of violence were so stark that it was frozen in my memory. I didn’t struggle while writing the copy,” he says, now stepping into the gurdwara that has a hall filled with pictures of the victims.

As he gets back onto the lanes of Trilokpuri, hoping to find familiar faces amidst the rush of people, he is disappointed — most of the families have moved out.

Surjeet Kaur’s is among the few families who stayed behind. Now 83, Kaur talks of the “Indira kand (case)” impassively, barely blinking her glassy eyes. “Fifteen members of my family hid in the home of a Hindu family for three days. Two of our relatives died,” she says, sitting in her Block 30 home. “All this was destroyed, meri bahu ka dahej bhi (my daughter-in-law’s dowry too).”

In a parallel lane, Kanwaljit Singh Sandhu, 47, struggles to hold back tears as he talks about his brothers, 12 and 18 then. “They were beaten with rods, burning tyres were put around their necks and some inflammable powder was thrown on them. I was attacked with swords. Both my hands shake even now,” says Sandhu, who was 13 then. He relies on money from rent to provide for his wife and two children.

No Sikh families live in Block 32 now. (Express Photo: Neeraj Priyadarshi)

No Sikh families live in Block 32 now. (Express Photo: Neeraj Priyadarshi)

The colony then, says Maliakan, was made up of one-room tenements. “A lot of this haphazard construction has happened over the years and people have been renting out houses. The lanes are also much wider now. Earlier there were open drains on both sides of the narrow lanes, there was no sewerage system in place,” he says.

In Block 32, children run around, playing games. A few youngsters zip around on their bikes, some others stand in street corners taking selfies. As he walks through the block, with occasional streams of sunlight slipping in through the randomly built four-storey buildings, Maliakan takes a break, settling down on the steps leading up to a building. A few women peep out from their homes.

“On the night of November 2, I reached office around 2 am. I got a lift in a police vehicle and then walked for 20 minutes to get there. When I told my editors about the scale of the violence, they were shocked. I was grilled for long. I insisted that more than 400 people had died. Later, after several rounds of verification, we pegged the death toll, if I remember right, at 395,” he says. The Express copy of the following morning put the toll at 350.

“I slept in office that night and was back in Trilokpuri around 8 am the next day,” says Maliakan, his reporter’s eye now spotting a woman selling illicit liquor in one of the homes down the lane.

The next day, on November 3, when Maliakan reached Trilokpuri, the tree trunk barriers had gone. But the violence was yet to end. “In the first lane of the colony, I saw a Sikh man being pulled out of his home and being burnt alive by five-six men in front of his wife. Small groups had returned to check if any Sikh men were still alive in the area. They were clearing them out,” says the 70-year-old.

By November 4, the carnage in Trilokpuri was over, but the journey to safety was a long and tough one. “Over the next few days, most police stations in East Delhi turned into camps. I visited the Kalyanpuri police station nearby. It was overflowing with people — shocked, stricken with grief, begging the police officers for help. But they did little.”

***********

A year after the riots, refugees from Trilokpuri, about 600 of them widows, were allotted homes 30 km away, in Tilak Vihar, which over the years has come to be known as ‘Widows’ Colony’.

In the neighbourhood’s congested homes and dingy lanes, Maliakan is hoping to find some old friends, whose paths crossed with his during and after the riots — ‘Inder Kaur’ in particular, who had pleaded to him for help that night on November 2. “I met her last two to three years ago. She was very ill and bed-ridden then,” says Maliakan, looking up at the homes hoping to see Inder Kaur, hoping she would stick her head out of one of the windows and he would spot her.

Maliakan strikes a conversation with a group of women sitting on the side of the road and soaking in the winter sun, picking saag (greens). Seventy-year-old Dalbeer Kaur recognises Maliakan. “He comes here for the memorial ceremony sometimes,” she smiles.

When Maliakan asks her about Inder Kaur, she brings along a 55-year-old woman of the same name. “Not her,” says Maliakan, shaking his head. He moves to another lane to ask people about Inder Kaur.

As the sun begins to set, and Maliakan prepares to leave, he says, “Maybe I am forgetting her name, maybe it wasn’t Inder Kaur… Maybe she is no more.”

(Maliakan worked with The Indian Express between 1979 and 2006. He now works as a guest lecturer at journalism colleges in Delhi-NCR. He filed an affidavit before the Ranganath Misra Commission on the 1984 riots)

The probe bodies

By Abhishek Angad

Justice Ranganath Misra Commission, 1985

Appointed by prime minister Rajiv Gandhi to inquire into the “organised violence” in Delhi and outside after the assassination of Indira Gandhi. While calling police “indifferent or negligent”, the Commission said that the Congress party or its leaders had not participated in the riots, even though “some persons belonging to the Congress party on their own did indulge or participate in the riots for considerations entirely their own”.

Kapoor-Mittal Committee, 1987

The panel with Justice Dilip K Kapoor and a retired secretary to the Government of India, Kusum Lata Mittal, could not function due to differences of opinion between the members. It was set up to inquire into the delinquencies and conduct of police officers of Delhi. Mittal submitted her report on February 28, 1990; Justice Kapoor submitted a separate report the following day. The Home Ministry found Justice Kapoor’s report to be a sociological analysis dealing in generalities, and decided to accept Mittal’s report and take action against police officials on the basis of its findings. Seventy-two police officers were indicted for lapses in controlling the riots.

Jain-Renision Committee, 1987

Set up to look into allegations of grave offences committed during the riots.

R K Ahuja Committee, 1987

Set up to establish the exact number of deaths that took place in Delhi. After detailed inquiries, the Committee determined that 2,733 deaths had occurred in the Capital.

Justice J D Jain and retired IPS officer D K Aggarwal Committee, 1990

They took up 669 affidavits filed before the Justice Misra Commission, received 415 new affidavits, and also looked into 403 FIRs recorded by the Delhi Police. The Committee found that no separate FIRs were recorded for individual incidents, no case-by-case investigation was carried out, and no incident-wise evidence was produced during the trial, leading to acquittals in most cases.

Justice Nanavati Commission, 2000

The Commission examined the first witness in the case on April 17, 2001, and completed the recording of evidence on March 12, 2004.The Commission recommended that the Central government ensure that all victims are “paid compensation uniformly at an early date”, and consider giving a job to one member of each family “that had lost all earning male members” and had no other “sufficient means of livelihood”. But the Commission recommended the re-opening of only four out of 241 cases closed by police.

Pramod Asthana SIT, 2015

Appointed by the Home Ministry, the SIT closed 186 riot cases. After over two years of investigation, the SIT filed chargesheets in only 12 cases.

Supreme Court-appointed SIT, Jan 2018

To re-investigate the 186 cases related to the riots, which were closed by the government-appointed SIT.