Sixty-five years ago, India and Pakistan signed the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT). Brokered by the World Bank, it divided a collection of rivers into two “national” halves. The western rivers flowing from J&K — Chenab, Jhelum, and the Indus — were for Pakistan’s use, while the eastern rivers in Punjab — Sutlej, Beas, and Ravi — were assigned for India’s exclusive utilisation. The divided Indus Basin was to be governed by provisions, restrictions and arbitration mechanisms. In the post-colonial imagination, the Indus and its tributaries were claimed as instruments of nation-building, valued in terms of sovereignty.

When the Lok Sabha debated the IWT on November 30, 1960, the mood was anything but celebratory. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru faced sharp criticism. One member accused him of acting like “an umpire in a cricket match” whenever India was in dispute, rather than defending the country whose destiny he led. Nehru, true to his temperament, appealed to higher ideals, dismissing what he called the “narrow-minded spirit” of the House.

While the engineers behind the treaty offered a technical solution to optimise the basin’s waters, the larger political purpose that Nehru had invested in it — peace and stability with Pakistan — quickly unravelled. Barely had the ink dried when Pakistan’s President Ayub Khan turned the very logic of the treaty on its head. If the

western rivers were Pakistan’s share, he argued, then Pakistan’s claim to Kashmir was only natural, since those rivers flowed through its territory. What Nehru envisioned as a bridge to peace, Ayub swiftly recast as a lever of contention — an awakening that, treaty or no treaty, Pakistan’s aggression towards India would persist.

History carries weight, but it cannot be undone. The real test is not whether the treaty was right or wrong in 1960, but whether it still matters today. Terror attacks and political hostility have reduced the notion of shared resource management to a hollow idea. After the Pahalgam attack, India put the IWT in abeyance, suspending its participation in its mechanisms.

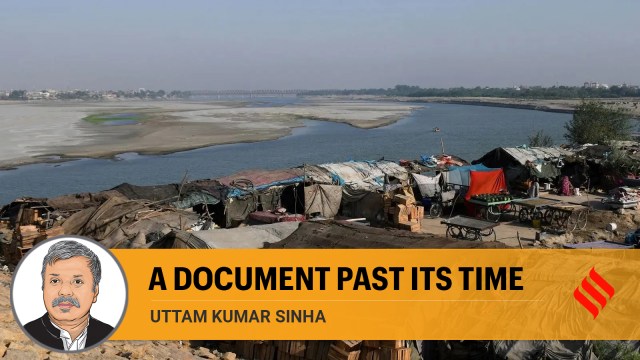

The rivers continue to flow — indifferent to politics. But the challenges confronting the Indus Basin today are unlike any before, rendering the IWT a document of the past.

Climate change is accelerating glacier melt in the Hindu Kush–Himalaya, directly affecting water availability. In the Upper Indus Basin, glaciers are shrinking, and runoff is projected to rise, bringing major shifts in river flows. Further downstream, in the Lower Indus Basin, rainfall has grown increasingly erratic, with the once-reliable monsoon transforming from agriculture’s trusted ally into an unpredictable threat.

The devastating floods in Punjab this year were not mere natural disasters; they were warnings of a new hydrological reality. The floods have affected 1,650 villages in all its 23 districts and have submerged over 1.75 lakh acres of farmland, causing massive damage to paddy and other crops. Across the border, in Pakistan’s Punjab province, over two million people had to be evacuated as the waters rose. The Indus Basin is under extraordinary strain, far beyond the reach of any treaty clause.

Alongside climate extremes lies a silent crisis — siltation. Reservoirs are choking, storage capacity shrinks each year, canals carry less water, and rising riverbeds make floods fiercer. These are not distant problems; they are unfolding in real time. What the rivers need is not piecemeal dredging after each flood or ad-hoc desiltation when reservoirs clog, but a coherent national strategy on silt management.

In Punjab, the problem has taken on urgent proportions. Floods this year left large tracts of farmland buried under silt, crippling farmers who had already lost their crops. The broader lesson, however, is clear: Siltation is not just a by-product of floods — it is a growing national crisis, one that demands a long-term, coordinated response. Silt must be seen not as waste but as a resource. It can enrich soil, support construction, and aid land reclamation. A national effort to manage silt could reduce floods, expand storage, and make water use far more efficient.

The IWT was forged in an era when water was about canals and hydropower. At the time, the priority was irrigation projects, dams, and the mechanics of resource division. But today, water has taken on a very different meaning. It is no longer only about engineering rivers; it is about resilience in the face of climate extremes, preparedness for disasters, and the sustainability of fragile ecosystems.

So what of the treaty? Many would argue that it is as good as dead. The mechanisms it once embodied — allocation of rivers, adjudication of disputes, regulation of projects — no longer address the challenges at hand. What truly matters today is not the fine print of a 1960 agreement, but the sharing of transboundary hydrological data and timely flood information. A detailed, rigid treaty is unnecessary; what is needed is a lean, functional framework, even something as simple as a Memorandum of Understanding. India already has such an MoU with China on hydrological data from the Brahmaputra, which has proved effective during monsoon floods.

In fact, data exchange was always embedded within the IWT, and India, despite political hostilities, has adhered to it with consistency and discipline. This is where the future lies — not in clinging to a text that has lost relevance, but in enabling the flow of information, because in a climate-stressed world, data saves lives.

The 65th anniversary of the Indus Waters Treaty calls for clear-eyed scrutiny. A treaty cannot endure without dialogue, nor can a framework from 1960 withstand the shocks of the 21st century. Equally, India cannot afford to ignore choking rivers in the absence of a national siltation policy. To dwell on blame while neglecting preparation for the crises ahead is futile. These are not abstract questions — they touch directly on the survival of millions across the Indus basin.

The writer is Senior Fellow at Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses and author of Trail By Water: Indus Basin and India-Pakistan Relations