Opinion Out of my mind: About time

Bhagwat’s sense of timing is terrible coming so close to the Bihar elections. Even so, it is legitimate to raise the question of how long will reservations last.

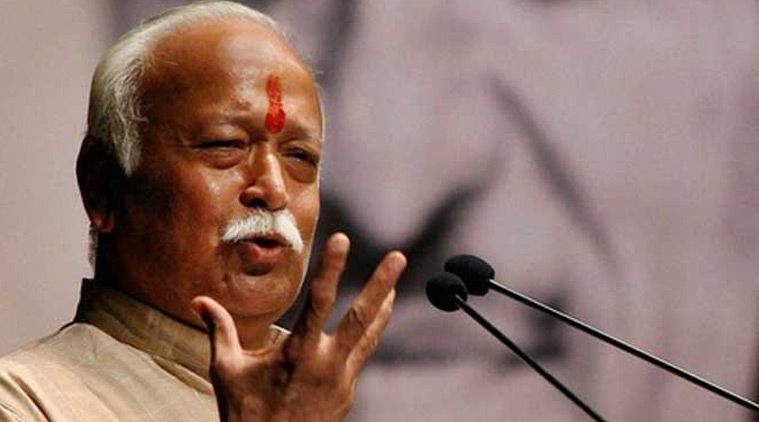

RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat.

RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat.  RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat.

RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat.

When in 1991, the Rao government liberalised the economy, there were howls of anguish from India’s industrialists. They had enjoyed socialist protection. Now they faced capitalist competition.

Unfair, they said. Not yet ready. Luckily, they were ignored and India (as well they) thrived. Now Mohan Bhagwat has opened a can of worms asking whether it is time

All the groups who have enjoyed reservations are against, as are all political parties chasing caste vote banks. Bhagwat’s sense of timing is terrible coming so close to the Bihar elections. Even so, it is legitimate to raise the question of how long will reservations last.

Some form of positive discrimination began early in the last century. Once the British had granted even limited franchise, then demands to curb Brahmin monopoly of the best jobs became urgent.

In the old Madras State, the Justice Party ran an effective anti-Brahmin campaign. The Brahmins had denied education to the rest until the British established schools open to all. The newly educated wanted good government jobs.

In 1931, at the end of Round Table Conferences, thanks to B R Ambedkar’s lobbying, a white paper listed the castes and tribes which needed special treatment. Thus we had the category of SC/ST.

The Constitution promised reservations to SC/ST for 15 years. Of course, the reservations continued. Then during the Janata government, the Mandal Commission was appointed. The need was clear. By then 30 years of Independence and 25 years of Planning had generated a stagnant economy with top-heavy industrialisation and little growth in employment for those outside the charmed circle of English-medium educated upper caste graduates. The overwhelming majority of Indians had not benefited from the Plans.

The Mandal report located social deprivation among the lower castes, especially the Shudra jaatis — OBCs.

But Mandal only looked at Hindu caste society. Even if one assumed that the Dalits were taken care of, the other minorities, especially Muslims, were ignored. The Sachar report commissioned by the UPA government but not implemented tells us how deprived Muslims are.

When the Congress lost hegemony in 1989, implementation of Mandal became possible. Neither the Congress nor the BJP liked it, but gave up in the face of mass demand. So the Rao government moved on two fronts — Mandal to repair the damage of decades of stagnation and liberalisation to get growth going.

Now, a century later, surely it is time to ask, ‘Has it worked?’. Politically, the success of reservations is shown, if perversely, by the Patidar agitation. Limits of the reservation policy have thus been reached. Groups like Jats and Patidars are technically OBC but they advanced their economic and social status by skillful land management and embracing western education. They are not socially deprived in any sense.

The Mandal OBCs are mainly among BIMARU states, where the economic stagnation of the 30 years after Independence was reinforced by oppression by upper castes, which had a strong presence in the Congress.

We now have a caste census. It is time to examine whether the jaatis pinpointed by Mandal and among the Dalits have improved their relative status. Modi tackled the 42-year-old OROP issue. At the very least, he should ask an expert committee to see if a century of reservations has worked.

Not now. After Bihar.