Opinion Remembering B V Doshi: The architect who opened new windows to see the world

A man with an infinitely curious mind, he believed that a good design had to be all encompassing, a unified whole, like a living being.

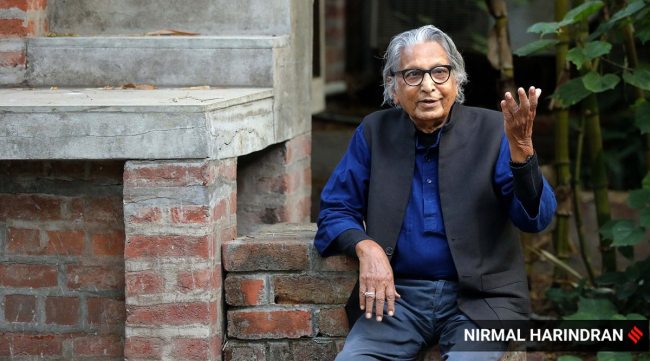

While life threw challenges at him, of unfinished buildings or clients who never returned, BV Doshi began questioning the meaning and purpose of architecture. (Express file photo by Nirmal Harindran)

While life threw challenges at him, of unfinished buildings or clients who never returned, BV Doshi began questioning the meaning and purpose of architecture. (Express file photo by Nirmal Harindran) There is a fundamental change that architecture brings within us, in the way we experience the world when we enter a building or a space. A double-height ceiling can make us feel like royalty while a room without a window can make even the sunniest day feel dreary. We seldom think about what four walls and a floor can do, but when you’re in a room, you can drape it with the finest linen and the warmest kilims and yet feel incomplete if it doesn’t show you a bit of the sky.

One person who knew how to choreograph spaces was BV Doshi, who passed away on Tuesday. He’s the first Indian architect to win the illustrious Pritzker Architecture Prize (2018) besides a slew of other awards, including the Padma Bhushan (2020) and, more recently, the Royal Gold Medal 2022 presented by the Royal Institute of British Architects.

Three things worked for Doshi in his nearly seven-decade-long career: The trust of clients like Kasturbhai Lalbhai and Vikram Sarabhai that became his diving board; his moral and intellectual values; and his infinitely curious mind, which allowed him to learn from everyone and everything around him. He was known to keep a notepad and sketch or write anything new he saw or heard, often revisiting it and allowing it to enter his work.

In his biography, Paths Uncharted, he wrote about how Sarabhai defended his project for the Electronic Corporation of India, Hyderabad, in 1974, where he suggested mixing income groups and varying the unit sizes. Doshi would expand that idea into his award-winning Aranya low-cost housing project in Indore, where common areas were connected and people could appropriate spaces, because of the malleable plan in the design. What was meant to be only an infrastructure project became a social one, where housing was not seen as an end product but as a process.

While life threw challenges at him, of unfinished buildings or clients who never returned, Doshi began questioning the meaning and purpose of architecture. His Ahmedabad studio, Sangath, is an answer to that question. A good design had to be all encompassing, a unified whole, like a living being, he said. Sangath breathes that life into that mix, hedged by plants and including water bodies, a place where you get lost before you find the entrance. He spoke of how Sangath was the sum of his life’s journey, the experiences he had, the places he visited and worked in. It could be found in the mezzanine, as one climbs a ladder from a workstation to get there, in the skylights on vaults, in the water channels that cool down the area — each aspect of Sangath’s design contributes to the overall vocabulary of the sunken building.

Doshi was not impervious to change. In the book, Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People, he writes about the elasticity of time and moment. How the pedestrian scales of a village have to come to terms with eight-lane highways and the quiet of trees and courtyards have to accommodate the sounds of televisions and vehicles in every home. “Very often, the small, sometimes allegedly uneconomic, but beautiful scale has to find a place for itself in the supposedly efficient large scales of settlements…it is these diverse forces that give an object or environment their timeless quality…Spaces must establish a dialogue with the physical and merge with the metaphysical through a celebration of activities.”

One of his favourite examples of fluidity comes from a childhood memory of rain. On a particularly hot sultry day, the sky was overcast and everyone hoped for some showers. Soon, as rain drops pelted on tin roofs, children ran out to greet the showers, elders emerged from sleepy verandas to shut windows and pick up clothes from the terrace, while from the kitchen could be heard the gentle sizzle of pakoras frying. The entire house, he says, had rearranged itself around the rain.

When he won the RIBA Award, Doshi told The Indian Express, “The whole sense of being an instrument of change has to do with allowing things to take shape as nature does. You may not know it at that time, but when it bears fruit, you will be surprised.”

Not often does one meet people who impress upon life not only through their creative energies, but also by opening new windows for us to see the world, and showing us how the world touches us on the inside. Doshi was one such person.

shiny.varghese@expressindia.com