Opinion Why Communist Party of China and RSS must talk to each other

They must understand each other better to reduce knowledge and trust deficit between India and China

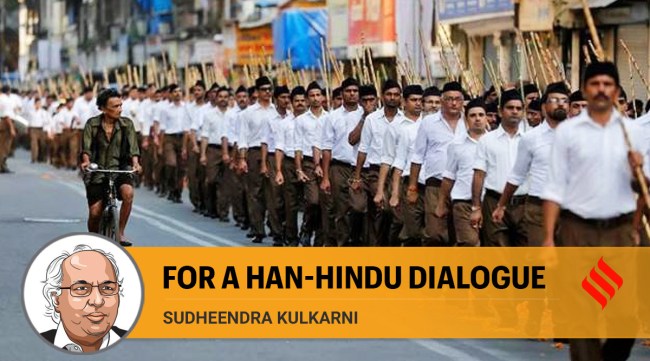

The visit would have two benefits. One, Chinese leaders will know the mind of India’s most influential Hindu organisation. Two, Bhagwat will better understand the factors behind China’s meteoric rise and also the deep appreciation many Chinese people have for India’s spiritual and cultural heritage. (Express Photo)

The visit would have two benefits. One, Chinese leaders will know the mind of India’s most influential Hindu organisation. Two, Bhagwat will better understand the factors behind China’s meteoric rise and also the deep appreciation many Chinese people have for India’s spiritual and cultural heritage. (Express Photo) Can the China-India civilisational dialogue — specifically, the Han-Hindu dialogue among the majority communities in our two countries — help in improving the current tense bilateral relations? I am convinced that the accumulated wisdom of the ancient civilisations alone can guide our two nations towards mutually acceptable solutions to the vexed problems that have hindered cooperation.

Therefore, here is a plea for an open-minded dialogue between the Communist Party of China and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, whose ideology influences the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party.

Therefore, here is a plea for an open-minded dialogue between the Communist Party of China and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, whose ideology influences the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party.In May 2019, I participated in the Conference on Dialogue of Asian Civilisations hosted by the Chinese President Xi Jinping in Beijing. The Government of India gave it a miss, which it should not have. In his speech, Xi, who has recently proposed a Global Civilisation Initiative, paid rich tributes to all the civilisations in Asia. He made a surprising observation: “The thought that one’s own race and civilisation are superior and the inclination to remould or replace other civilisations is just stupid, and will only bring catastrophic consequences…What we need is to respect each other as equals and say no to hubris and prejudice.”

Another surprise awaited me when I received from the organisers of the conference the book, China: A 5,000-Year Odyssey by Tan Chung. It describes how India influenced China in ancient and mediaeval times. The author’s candour is of the kind that one does not expect in a Chinese government publication. “The civilisations of China and India are the twins of the Himalaya sphere. How unfortunate that the progress of the two civilisations turned Mother Himalaya into a battleground! The two ‘civilisation-states’ that advocated ‘Panchsheel’ (five principles of peaceful co-existence) today behave like ‘nation-states’, maintaining a tit-for-tat armed coexistence. A greater tragedy of history I have not seen! Both countries have committed blunders and are responsible for righting this historic wrong.”

Tan Chung is eminently qualified to say this. A renowned Chinese scholar on the history and culture of both countries, he taught at Jawaharlal Nehru University. His father Tan Yun-shan, known as the “modern Huen Tsang”, came to India in 1928 at the invitation of Rabindranath Tagore, set up the Cheena Bhavana at Viswa Bharati, and lived in India until his death in 1983.

Countless milestones mark the journey of civilisational affinity between India and China. Sadly, these are now ignored, even denied and derided, because of the current fraught bilateral relations. Here are a few examples. India is currently celebrating Sri Aurobindo’s 150th birth anniversary. But how many Indians have heard of the name of Xu Fancheng, a Chinese scholar-devotee of Aurobindo, who lived in his ashram in Pondicherry for 28 years, translated the Upanishads and other Hindu texts into Chinese and also wrote books to introduce Confucius and other Chinese philosophers to Indians? How many in the Ram Janmabhoomi movement know about Ji Xianlin, revered in China as a “Gurudev”, who translated the Ramayana into Chinese and devoted his entire life to producing works that illuminate the Buddhist-Hindu links between our two countries? In their book Ji Xianlin: A Critical Biography, Chinese scholars Yu Longyu and Zhu Xuan describe him as “the mirror of our times, the conscience of our society, the benchmark of the academia, and the treasure of our nation.”

Yu, with whom I have interacted for many years, heads the Centre of Indian Studies at Shenzhen University, where he has created a marvellous museum in honour of Tan Yun-shan. At its entrance is a large frame with an inscription in Sanskrit of “Prajnaparamita Hridaya Sutra” (Heart Sutra), the most sacred Buddhist sutra in Chinese Buddhism. “Why is this in Sanskrit?” I asked. Yu replied in fluent Hindi, “Sanskrit is very dear to the Chinese because it is the language of the enlightenment that came from India. I know of wealthy Buddhists in Shanghai and other cities who frequently travel to Hangzhou to learn Sanskrit at one of the oldest monasteries in that city.” When I visited that vast Buddhist shrine called Lingyin Temple in Hangzhou, I was surprised to know that it was founded by a Hindu monk from India, named Matiyukti, nearly 1,700 years ago.

Beneath all the glitter of Western-style modernity, today’s China is eagerly seeking to re-discover its own proud philosophical and spiritual traditions. Isn’t modern India also engaged in a similar search? Therefore, reducing both the knowledge deficit and trust deficit between our two countries is the need of the hour, and this requires extensive, serious and sincere interaction among CPC and RSS leaders. I call it the “Han-Hindu Dialogue”, not because non-Hindus in India and non-Han races in China do not matter. Indeed, the journey of Islamic influence from India to China is another fascinating story. Clearly, our two countries should rededicate themselves to our precious but often neglected ethos of respect for diversity and commitment to mutual learning.

Both India and China aspire to become world powers commensurate to the innate potential of their respective civilisations. But why should these legitimate national aspirations conflict with, rather than complement, each other? True, the RSS is not the sole voice of India’s national aspirations; nevertheless, it is an important voice. Therefore, I have often suggested to high-ranking officials in Beijing that they should invite RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat to visit China. Their response was positive. The visit would have two benefits. One, Chinese leaders will know the mind of India’s most influential Hindu organisation. Two, Bhagwat will better understand the factors behind China’s meteoric rise and also the deep appreciation many Chinese people have for India’s spiritual and cultural heritage. Surely, his visit will help reduce the differences between our two nations and partly contribute to breaking the present logjam in ties.

The writer was an aide to former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee