When Atal Bihari Vajpayee was called ‘Nehruvian in Jan Sanghi garb’: New book traces their complex relationship

The Ascent of the Hindu Right 1924-1977' talks of BJP leader's support for Nehru during 1962 war and his admiration as a young man for the latter, but debunks that Nehru ever saw him as future PM

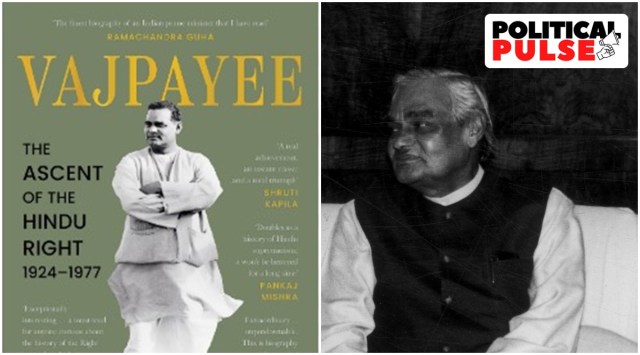

(Left) Authored by Abhishek Choudhary and published by Pan Macmillan India, this book charts Vajpayee's early years in parliamentary politics.

(Left) Authored by Abhishek Choudhary and published by Pan Macmillan India, this book charts Vajpayee's early years in parliamentary politics.

Atal Bihari Vajpayee, the country’s first prime minister from the RSS and Jana Sangh background, was dubbed a “Nehruite” during the Sino-Indian conflict in 1962, according to a new biography of the BJP’s iconic face.

In his book, “Vajpayee – The Ascent of the Hindu Right 1924-1977”, author Abhishek Choudhary writes that Acharya J B Kripalini, unhappy with Vajpayee’s refusal to call for Nehru’s resignation as the PM in the wake of the China-India war, made this jibe at a rally.

“Irked, Kripalini declared Vajpayee to be a Nehruvian in Jan Sanghi garb. At a rally held by the non-communist opposition on November 7, 1962, Kripalini warned the Swatantra Party leader Minoo Masani: ‘Don’t trust that man, he is essentially a Nehruite, and not one of us’,” says the book, published by Pan Macmillan India, which charts Vajpayee’s early years in parliamentary politics.

However, the author adds that Kripalini’s remark was born out of “prejudice” as Vajpayee’s differences with other Opposition leaders on this question were more “semantic rather than qualitative”. “Vajpayee simply felt that to ask Nehru to resign – in the middle of a war, and only six months after he had been returned to office with a two-thirds majority – was a fatuous, impractical proposition,” notes the author.

The book is however also replete with accounts showing a young Vajpayee’s quiet admiration for Nehru, especially in its chapter titled “Beloved Nemesis: The Nehru Years”.

On his part, Nehru, who was 68 years old when Vajpayee first got elected to the Parliament as a nominee of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS), the BJP’s erstwhile avatar, at the age of 32, was not dismissive of the young MP, who he thought was a “likeable, bright young man in an otherwise regressive party”.

However, Nehru never prophesied a prime ministership for Vajpayee, Choudhary writes, seeking to debunk this claim made by many in the past. His book points out that Vajpayee managed to elicit a response from Nehru, albeit a stinging one, soon after he entered the Lok Sabha for the first time in 1957 by winning from the Balrampur seat (now scrapped) in Uttar Pradesh.

In his first Lok Sabha speech on May 15 that year, Vajpayee criticised Nehru on many counts, including on the latter’s Kashmir policy. “Would we liberate one-third of Kashmir by sending the army? No no. Would we gift it away to Pakistan? No no…Would we take police action in Goa? No no. Would we then permit a satyagraha there by our people? No no. Would we leave Goa to Portugal’s mercies? No no,” the book quotes Vajpayee as having said in his speech as Nehru listened silently.

The next day, in his response, Nehru referred to Vajpayee as a “’new netaji from our opposition party’ who was good only at churning out platitudes”. “Unke hathiyar mujhe zara baazaru maalum hue…Election still bears heavy on his mind, it seemed he thinks of the Lok Sabha too as an election meeting,” Nehru quipped.

The book says that PM Nehru got Vajpayee included in a list of the Indian delegates for the United Nations General Assembly session in 1960. At that time, Vajpayee was headed to the United States, in his first foreign trip, on the invitation of the US government to be present as an observer during the then presidential polls in which Democrat John F Kennedy and Republican Richard Nixon were locked in a contest.

During his stay in New York, Vajpayee was mostly in the company of a foreign service officer posted in the permanent mission of India to the UN, M K Rasgotra, who would later go on to serve as India’s foreign secretary. Rasgotra, who was instructed by Nehru’s office to introduce the first-time visitor to leaders from all continents so that he “gets a sense of how the real world works”, told the author that he felt Vajpayee had “very high regard for Panditji” and there was “quietly a relationship, sort of, building up between the two”.

Both in their early thirties then, Rasgotra and Vajpayee also shared some light camaraderie during the trip, as the young diplomat took the first-time MP to museums and art galleries, which “did not evoke any great interest” in Vajpayee, as well as nightclubs.

“It was not clear to Vajpayee what a nightclub was exactly. Rasgotra assured him that it was not a strip club: ‘Nagn nritya nahin hota hai. You would get to see what shape modern music is taking – there is jazz, instrumental, local music.’ Vajpayee got excited: ‘Chaliye, ye bhi ek nayi duniya hai.’ On such informal outings he drank a peg or two. But there were real limits to how informal Vajpayee could get with his companion. He did not confide in Rasgotra about the ongoing tumult in his private life,” states the book.