‘I turned Lichess into Google Drive’: 18yo shows how to store files, secret messages in a game of chess

Fair warning: it's probably illegal.

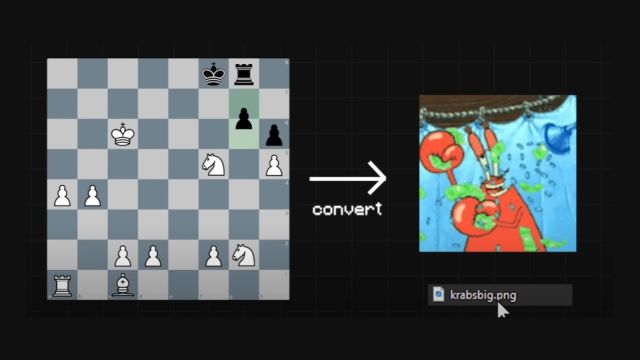

Screengrab from the YouTube channel of 'Wintrcat', showing how to use chess games as a form of cloud storage.

Screengrab from the YouTube channel of 'Wintrcat', showing how to use chess games as a form of cloud storage.There is a moment in ‘The Queen’s Gambit’ when Beth Harmon, the bright protagonist, is quizzed by the CIA on whether her opponent is sending her secret messages via the chessboard. Harmon scoffs at the idea. Viewers, no doubt, must’ve also found it ludicrous. But little did they know that one day, with a bit of creativity, this could become entirely possible.

Enter Wintrcat—or Wilson—an 18-year-old programmer whose ‘free cloud storage’ hack by using chess games is slowly going viral. Be warned: this is not a practical solution in any way; if you pay a premium for Google Drive, this is no replacement. But the ingenuity behind Wilson’s idea, using technology that has existed for at least a decade, has impressed many. Here’s how it works.

Wilson takes a file (here, a picture of Mr Krabs from Spongebob), and converts it into binary: pixels become zeroes and ones, so that computers can understand this data. Then, to stay within the guidelines of chess, he converts the binary into individual, legal chess moves. This file of moves is uploaded to Lichess, after which Wilson sets up two bot accounts to ‘play’ these moves for as long as necessary. Once a match ‘ends’, Wilson has essentially uploaded the data representing the image of Mr Krabs onto Lichess, making the chess site a free storage host. The file can then be decrypted and downloaded, as he shows below:

Is this an efficient storage hack? Not really. Wilson’s 9 kilobyte file—the size of a barebones .txt file—took 90 minutes to upload, requiring 19,758 moves played across 98 chess games. The upload speed was an infuriating 2 bytes per second, which is half the speed of 2G services. Nor is there any true spy-like merit here: you cannot safely pass any sensitive messages through these chess games, as there is no strong encryption to guard it.

But could you hide a sweet text message or image for your nerdy, chess-loving partner? Absolutely. “Make no mistake, it isn’t that useful past being kind of cool. But technically, this is still free cloud storage, because (depending on file size) you can have as many games as you want (auto-playing) on your account,” chuckles Wilson.

He adds that he selected Lichess for this experiment as it allows developers to set up bot accounts to interact with chess in creative ways. Lichess is an open-source website, where anyone can download, read, use and modify every bit of its source code. The same cannot be done for platforms like Chess.com.

Could ‘chesspionage’ be a real possibility?

Yes, if done a bit differently. Wilson’s idea broadly falls under steganography, which is the art of hiding information in an ordinary message/physical object without arousing suspicion. Simple examples of this are writing in invisible ink, or, say, combining four ‘random’ scribbles to make a sensible picture. The term was first recorded in 1499 in a book about magic—or so people thought! Polymath Johannes Trithemius had seemingly written his book, Steganographia, about using the spirits of the dead to communicate over long distances. It was only in 1606, when he published a decryption key, that people realised they had been fooled — he had actually written three volumes about cryptography.

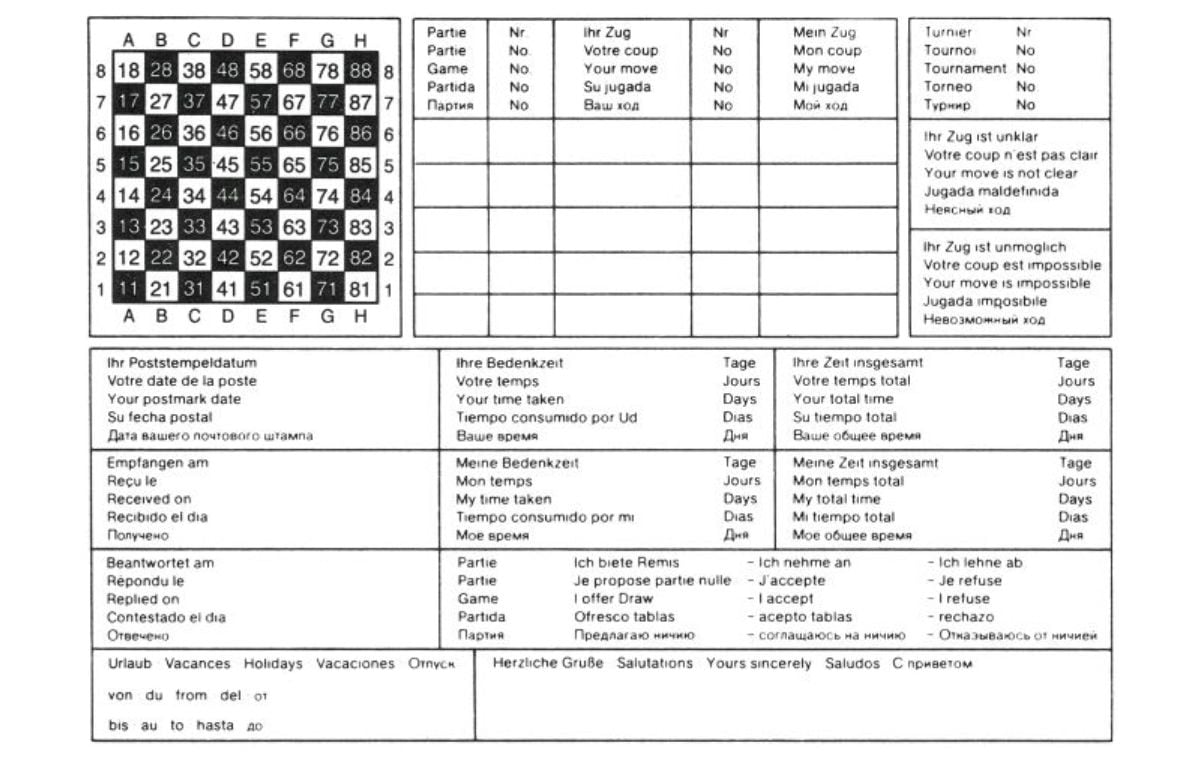

Coming to ‘chesspionage’ specifically, doubts of its existence rose during World War 2, when postal chess was a rising hobby for civilians and soldiers.

German postal chess card, circa 1930s-40s. (Lithium Flash/Wikimedia Commons)

German postal chess card, circa 1930s-40s. (Lithium Flash/Wikimedia Commons)

Here, players would mark their move on a postcard and mail it away, waiting for weeks, sometimes months, for their opponent’s reply to arrive in similar fashion. The fun came to a halt when North American censors grew suspicious of transatlantic chess matches, and began blocking the board on cards received by US servicemen, lest they leak state secrets. The fears weren’t too far-fetched; creating and breaking innovative ciphers proved decisive during World War 2—think Alan Turing’s work, or the Navajo code created by the Dine tribe.

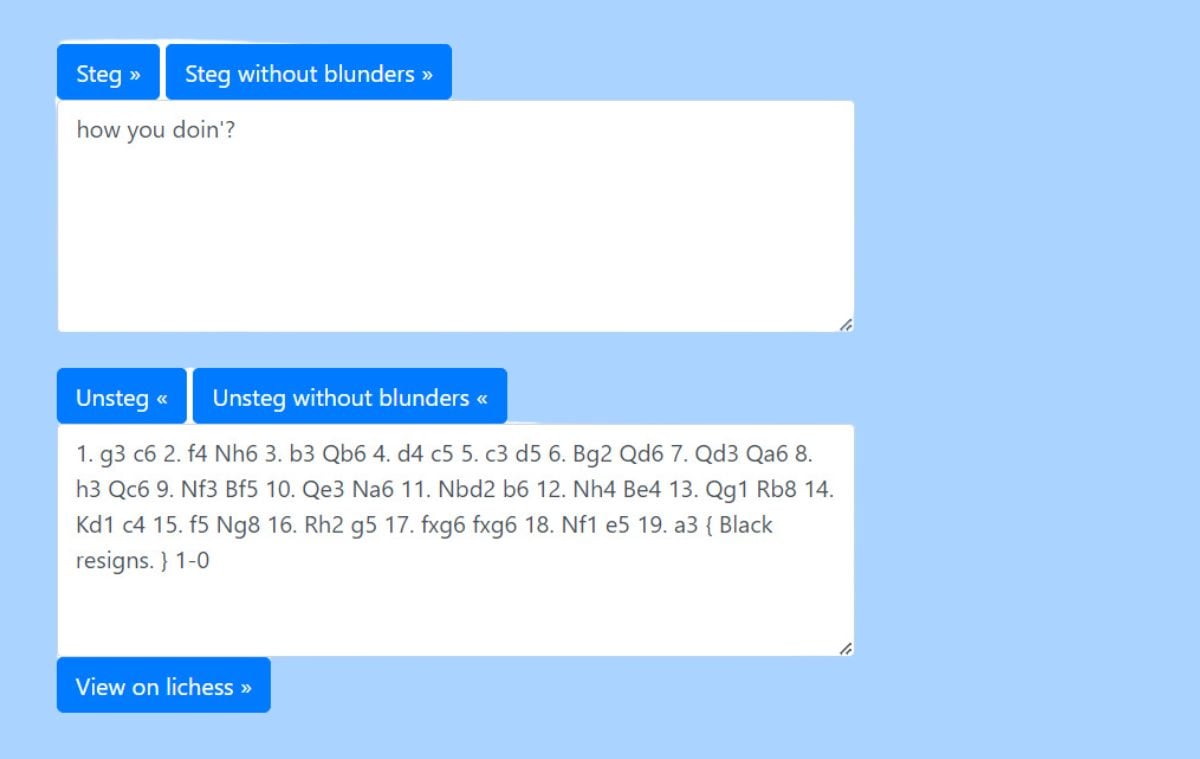

More recently, hobbyist puzzler James Stanley came out with a chess steganography game on his personal website. It’s akin to a translator: you type in a message, and out comes a list of chess notations for a match.

Chess steganography game by James Stanley, where secret messages can be encrypted as legitimate moves. (Courtesy incoherency.co.uk)

Chess steganography game by James Stanley, where secret messages can be encrypted as legitimate moves. (Courtesy incoherency.co.uk)

Knowing that seasoned players would be able to spot any intentionally poor decision-making in chess, Stanley’s game includes an option to use the p4wn chess engine to avoid making obvious blunders. This naturally stretches a ‘match’, but adds a realistic touch that could help pass a coded match under the radar withour raising eyebrows.

However, developing an eye for patterns, analysis and swift code-breaking takes time. If one tries making puzzles themselves, it can help jump the line when it comes to becoming a strong cryptographer. In India, those adept at such logical reasoning try their hand at the Indian Sudoku Championship held by Logic Masters India, or the International Linguistics Olympiad, where Indian teens recently earned top honours. Many move to careers in network security or intelligence in the future. As a gateway, you can explore our puzzles section, which features daily brainteasers for all ages. Happy solving!

Know more innovative uses of chess? Write in to puzzles@indianexpress.com and let us know! For more nerdy alerts, you can follow @iepuzzles on Instagram.