The Great Butter Rebellion to Israel-Gaza war unrest: The history of student protests in US

As opposition to the Israel-Hamas War engulfs college campuses across the United States, activists insist that while the methods and repercussions may differ, protesting is part of a long American tradition.

Thousands of students filled Sproul Plaza at the University of California, Berkeley, in April 1985 to protest the university’s business ties with apartheid South Africa

Thousands of students filled Sproul Plaza at the University of California, Berkeley, in April 1985 to protest the university’s business ties with apartheid South AfricaAlthough little is known about Asa Dunbar, he has been immortalised in Harvard lore as the instigator of America’s first student protest, the Great Butter Rebellion. As the legend goes, in September of 1766, disgusted by Harvard’s poor culinary standards, Dunbar mounted his chair and proclaimed: “Behold, our butter stinkith! Give us therefore, butter that stinkith not.”

Dunbar’s words were adopted as a motto by the student body. Many boycotted the Harvard Dining Halls. Administrators demanded names of the responsible. The students refused and half were suspended. After months of agitation, the Board of Overseers readmitted the suspended students and replaced the odorous butter, thus ending the Great Butter Rebellion.

Remnants of Dunbar’s diary were discovered in 1908 by E. Harlowe Russel, a biographer of Dunbar’s grandson, Henry David Thoreau. The diary revealed that Dunbar would go on to have a happy life, first as a minister and then a lawyer. However he would spend the rest of his days plagued by colic, a gastronomical disorder often caused by overconsuming saturated fat such as butter.

Harvard students continued Dunber’s legacy, protesting over ungutted mackerel and soggy cabbage alongside slavery, the Vietnam War, apartheid in South Africa, women’s rights and most recently, the Israel-Hamas war.

For centuries, the youth of America have lent their voices to a number of causes, the impact of which has been at times good, at times bad, and almost always, inconvenient.

Guns and Flowers

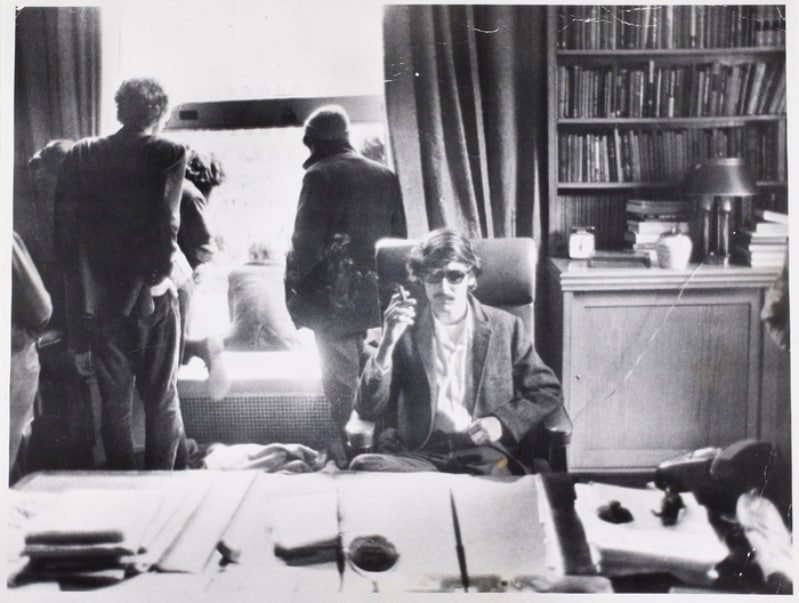

During the late 1960s, American Universities were alight with protests against the Vietnam War and the assassination of Martin Luther King. One photograph published by LIFE magazine shows Columbia student David Shapiro, who had barricaded himself inside the student-occupied office of University President Grayson Kirk. Wearing sunglasses, Shapiro sits on Kirk’s chair, his feet resting on his desk, while puffing away at one of the president’s cigars. When the police were called to evict the protesters, Shapiro was surprisingly spared and went on to receive one of Columbia’s most selective fellowships.

Student activist David Shapiro sitting behind University President Kirk’s desk smoking an appropriated cigar during six-day campus uprising and protest at Columbia University (The Life Magazine Collection)

Student activist David Shapiro sitting behind University President Kirk’s desk smoking an appropriated cigar during six-day campus uprising and protest at Columbia University (The Life Magazine Collection)

Decades later, Shapiro is remembered by the University as an icon, a visual reminder of Columbia’s affiliation with protests that shaped America. According to Mark Naison, who was one of the demonstrators in New York in 1968, most students were not as lucky.

In a conversation with indianexpresss.com, Naison, now a professor at Fordham University, paints a vivid picture of the scene. Unfolding over the course of multiple days, Columbia’s campus was besieged by student demonstrators and community members who had occupied five buildings on the campus. Counter protesters, primarily footballers and wrestlers, were intimidating black students and refusing to let food into the building. Fear of violent riots, which had taken place a month after the assassination of Martin Luther King, shaped everyone’s response to the protests, from university administrators to protesters themselves.

The police were called in to clear the occupied buildings, sparking a violent clash between law enforcement and protesters. In response, the whole community went on strike, and similar movements emerged on other campuses. Naison says, “Having that experience, when I saw police breaking up the encampments last week, I thought, here we go again.”

Naison is keen to stress that compared to the movements of his youth, the current protests have been relatively peaceful. In the first six months of 1969, there were 84 bombings and acts of arson reported on college campuses across the US.

The Ohio National Guard fires tear gas to disperse the crowd of students gathered on the commons at Kent State University, protesting the war in Vietnam, May 4, 1970 (Kent State Archives)

The Ohio National Guard fires tear gas to disperse the crowd of students gathered on the commons at Kent State University, protesting the war in Vietnam, May 4, 1970 (Kent State Archives)

In contrast, Olivia Kelleher, a graduate of the Annenberg School of Journalism, who is covering the pro-Palestinian protests at the University of Southern California, says that she has only noticed violence when the police have gotten involved. “I saw the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) marching into campus with zip ties, batons and less than lethal weapons, in full riot gear,” she says, adding that “the students were shocked but they voluntarily complied with the police.”

The law in this regard is clear. Protesters are protected by the First Amendment right to free speech. However, as journalist David French points out in an article for the New York Times published in May 2024, “what we’re seeing on a number of campuses isn’t free expression, nor is it civil disobedience. It’s outright lawlessness.” He argues that by occupying a public space, and by extension disrupting other students and preventing them from accessing that space, protesters are violating both the law and University policy. In that context, he states, “reasonable time, place and manner restrictions are indispensable.”

Still, the sight of armed police confronting students can be a disturbing one. Gyan Prakash, a professor of Indian history at Princeton University, tells indianexpress.com, that questions of law and order only arise when the University refuses to engage in dialogue.

Jim Kunen, author of The Strawberry Statement (1969), a first person account of the 1968 protests, echoes a similar sentiment. “I sympathise with the predicament administrators are in,” Kunen tells indianexpress.com, “but the answer isn’t to arrest students, it’s to have a conversation with them, hear their grievances, and create a space for them to make their voices heard.”

The 1968 protests occurred against the Joseph McCarthy era Red Scare. As Kunen states, protesters were being violently suppressed because they were seen as being a fifth column, of working against the United States and harbouring communist tendencies.

Officers of the law were equally forceful in 1960, when four teenagers from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University walked up to a Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, and refused to leave until the store was desegregated. Within three days, they were joined by some 300 others. By summer, the sit-ins had spread to more than 50 cities. One of the teenagers, Ezell Blair Jr, now a converted Muslim going by Jibreel Khazan, speaks about the adverse effects it had on his physical and mental health. “I did not want to get killed or beaten,” he says, “I was only 18. It just was, and is, the right thing to do.”

F.W. Woolworths in Greensboro, N.C., became a national symbol of the civil rights movement after students staged a sit-in at a segregated lunch counter (Bettmann, Getty Images)

F.W. Woolworths in Greensboro, N.C., became a national symbol of the civil rights movement after students staged a sit-in at a segregated lunch counter (Bettmann, Getty Images)

The fate of protesters today is much different. According to Kunen, when he was a student activist, every day he feared having to fight the war, go to prison or flee the country. Students against the Israel-Hamas war don’t have that same fear.

Prakash states that out of his class of 12, only one was Palestinian, yet all of them stood in solidarity with the cause. In his 30 years at Princeton, he states, he has seen a distinct change. “Students seem much more engaged and concerned with these broader issues,” he says, “which reflects an ethical commitment to the notion of justice.”

As one student from Occidental College told indianexpress.com, “Israel is a white supremist state, what they are doing to Palestinians is the same thing that America has done to African Americans and members of the LGBTQ community.” The student, who goes by they/them pronouns, and has declined to be identified, added that they joined the protests because they felt that it was the right thing to do.

Kelleher also points out that students feel marginalised and silenced by their University’s response to the protests. Citing the example of Asna Tabassum, the valedictorian of University of Southern California, who was prohibited from giving the commencement address at graduation because of security concerns, Kelleher says, “Rather than protect her, they chose to silence her.”

The school had previously been supportive of students expressing various ideologies, Kelleher says, but they were concerned about the optics of Tabassum speaking. “To silence a hijab wearing Muslim woman, came across as a dismissal of our freedom of speech, she says.” Another student, a PhD candidate at Columbia who chose to speak on condition of anonymity, said, “protesters are speaking truth to power no matter the repercussions — and there have been many, to say the least.”

Facing repercussions and confronting an issue that doesn’t directly involve them might seem confusing to some. However as David Shapiro wrote in one of his poems:

If one saves one butterfly, even with long wings,

one butterfly that has fallen into water, it may be said:

“He has saved the whole world.”

Or as Kunen eloquently puts it, “When a situation is intolerable, you should not tolerate it, you should take action.”

Witch Hunts

During the heydays of the Red Scare, people protesting any issue — from the Korean War to the treatment of black Americans — were deemed as anti-national. They were subject to surveillance by the FBI, were barred from major industries and were ostracised by their fearful peers. Elite universities like Berkley and Yale however, continued to argue that they would preserve the right to free speech. In the case of the latter, it could portray itself as a bastion of academic freedom, but only once it had removed all subversives from its ranks.

As President Charles Seymour said, “there will be no witch-hunts at Yale, because there will be no witches.”

Back then, and for much of the Cold War, the “witches” were the protesters. Today, some say the tables have turned. Carol Garber, a professor at Columbia University says that she has been penalised for her seemingly pro-Israel views. In an online Columbia Faculty Senate meeting, Garber raised concerns that certain protest groups were being funded by terrorist organisations. Before she could elaborate, she was muted.

In an interview with indianexpress.com, Garber states that she has received a lot of backlash for her comments, and has been alienated by some of her colleagues. Still, she stands by her decision to speak up. “While the rhetoric coming from the faculty and students is similar to that of past protests, I don’t think that it’s the same thing,” she says, “because we are not hearing the language of peace now.”

Students gather in front of the Hopkins Center to protest the Vietnam War in 1970 (Rauner Special Collections Library)

Students gather in front of the Hopkins Center to protest the Vietnam War in 1970 (Rauner Special Collections Library)

Khymani James, a 20-year-old junior at Columbia is one of the leaders of Columbia University Apartheid Divest (CUAD), the coalition group that is organising the school’s pro-Palestinian encampment. In January, he filmed a video of himself appearing in front of Columbia officials because of earlier anti-Semitic comments he had posted online. In the video, James compares Zionists to Nazis, stating that, “the existence of them and the projects they have built i.e. Israel, it’s all antithetical to peace. So yes I feel very comfortable — very comfortable — calling for those people to die.”

While James would be temporarily suspended by Columbia, CUAD seemed to minimise his words. A statement posted by the group reads, “Khymani’s words in January do not reflect his views, our values, nor the encampment’s community agreements…We are students with a right to learn and grow.”

This, according to Garber, is reflective of the exclusionary nature of the protests — a feature that was absent from the movements of the past. She says that “many students, particularly Jewish students have found the events to be very disturbing and frightening,” adding that many of them have been discouraged from attending class or walking around the campus. For this, she places the weight of the blame on the faculty, who are distilling complex issues in a simplistic way by “teaching various philosophical concepts that encourage students to think along the binary of either being an oppressor or being oppressed.”

Naison says that the allegations of antisemitism have played a huge role in how administrators have reacted to the protests. “Jewish students feel attacked and because of that prominent alumni, Congress and local officials are putting enormous pressure on the school in a way that doesn’t even compare to what was going on in 1968,” he states. Prakash agrees, noting that the influence of Jewish lobbying groups, and pro-Israeli politicians is creating a gap between the political and media elite, and the people on the ground. He states, “there is a very entrenched, and I would say, you know, politically orchestrated opinion equating anti-Zionism with anti semitism.”

Garber however, believes that Universities have not come down harshly on protesters, pointing to the fact that students who have been suspended and arrested are still participating in the graduation ceremonies, with one even speaking during a toned-down commencement.

‘The whole world is watching’

An Axios poll conducted in May this year indicates that 81 per cent of Americans support holding protesters accountable with 67 per cent saying that occupying campus buildings is unacceptable. Compare this with a 1961 Gallup poll, where 57 per cent of Americans said that campus civil rights protests would hurt blacks’ chances of being integrated into the South.

Protests always look better in the rear-view mirror, which, according to Naison, is why Columbia, now (after decades) proudly boasting its affiliation to past protests, is reluctant to embrace the current group of students.

While everyone “hates” protesters, their actions do facilitate change. According to Kunen, “In 1968 we used to chant “The whole world is watching”. And the whole world was watching.” Everything they did was being photographed and a lot of young people across the United States and beyond emulated their actions. Kunen, who briefly reported from Vietnam, also said that American soldiers there were very aware of the protests going on at home.

Students for Peace Against Involvement of America in War protest against WW2 (Getty Images)

Students for Peace Against Involvement of America in War protest against WW2 (Getty Images)

“Disorder creates a situation from which some new order can arise,” he says, “there was tumult and uproar in the late 60s and early 70s. And now, here we are 50 years later, and you see great advances in women’s rights, in gay rights, in minority civil rights.”

Following the Black Lives Matter Protests of 2015-2016, Bryn Mar College and Georgetown University changed the names of buildings that honoured slaveholders. The term master to denote residential advisors was dropped by Harvard, Princeton and Yale. Brown University pledged over USD 100 million towards efforts to diversify faculty. Protesters at the University of Missouri and Claremont McKenna College forced their president and dean, respectively, to resign over mishandling racial incidents.

However, Neil Sheehan notes in A Bright Shining Lie (1988,) protests may sometimes have the opposite effect than intended. Sheehan writes that the protests of 1968 helped elect Richard Nixon into the White House. Naison says that since most Americans hate protesters, especially “snobby rich kids from Columbia,” these protests could similarly help Donald Trump.

If Dunbar were alive he’d probably agree. You can’t have your butter and eat it too.