The Marathas in Bombay: A testament to ambitions in a city they couldn’t keep

The Marathas' legacy in Bombay is one of profound yet understated influence. While the British ultimately emerged as the architects of modern Bombay, the Marathas' campaigns in Salsette, their triumph over the Portuguese, and their attempts to assert control over the islands reflect their vital role in shaping the region’s early modern history.

The Marathas hold significant influence in the politics of Mumbai

The Marathas hold significant influence in the politics of MumbaiIn the early 19th century when the British were attempting to expand in the Indian subcontinent, they were faced with just one major regional power capable of destroying their emerging empire – the Marathas. Spread across several small kingdoms, from modern-day Tamil Nadu in the south to Gwalior in the north and Odisha in the east, the Marathas, at one point, were said to have occupied a third of the subcontinent.

Though the regime set in place by Chhatrapati Shivaji dissipated by the early 1800s, in Maharashtra, the Marathas continue to have a resounding presence. Ever since the birth of Maharashtra in 1960, 12 of the state’s 20 chief ministers have been Marathas, including the incumbent Eknath Shinde. Issues related to the Maratha community, including the heavily debated demand for reservation, consistently frame electoral narratives in the state’s polls.

In this four-part series, we will do a deep dive into the multi-faceted history of the Marathas and unravel some remarkable and unknown facets of the community’s evolution over the centuries.

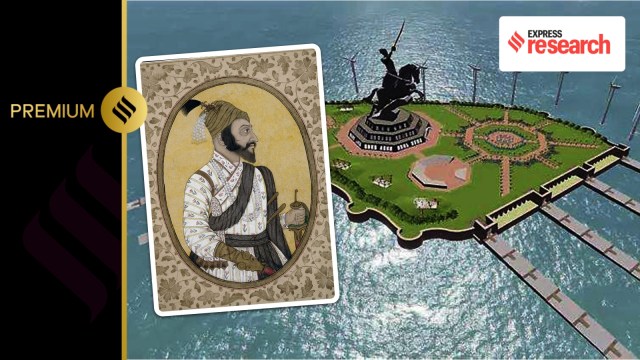

If one were to enter Mumbai via plane, they would most likely land at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj International Airport. Arriving by train, it would be through Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus. A tourist could spend their day lounging in Shivaji park or take in the cultural offerings of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Museum. In a few years, Mumbai’s iconic Bay may even be adorned by a statue of Chhatrapati Shivaji, which, according to current plan, will be one of the tallest in the world. In Maharashtra school textbooks, Shivaji is depicted as the founder of the state, his deeds and military exploits serving as a source of legend for children.

As Danish anthropologist Thomas Blom Hanson wrote in Violence in Urban India (2005), “The Shivaji mythology is a nodal point, the historical fiction at the heart of state practices, political rhetoric, and historical imagination in this part of India.” Loksatta editor Girish Kuber adds, “In Mumbai, Chhatrapati Shivaji is the most loved, amongst the political parties, left and right, and amongst the people.”

However, despite this popularity, it is often mentioned that Chhatrapati Shivaji never actually put any stock in Bombay. During his reign, and the reign of his successor Sambhaji, Bombay was a far cry from the city it is today. When one talks about the Marathas, they think of Pune, the Marathas’ expansion into the north, and their famed battles with the Mughals and Afghans. But while it is true that the Maratha presence in Bombay was limited and inconsistent, the city was very important in terms of the Marathas’ naval superiority under Chhatrapati Shivaji and Sambhaji, and its outer borough of Salsette was strategically significant for both the Portuguese and the British.

Maratha Navy

On land, the Marathas were initially dominant and succeeded in driving out their main rivals, the Siddis of Janjira. However, they were at a disadvantage when it came to naval power. During the late 17th century, the two battled fiercely for the Konkan coast which served as the battleground for competing powers. The British, Dutch, Portuguese and regional rulers, all vied for control over this lucrative strip of coast.

The Siddis dominated the waters around Janjira fort, their ancestral stronghold just off the coast of Alibaug. Recognising the need to compete navally, Chhatrapati Shivaji set up a Maratha naval force with the objective of destroying the Siddi clan. In A History of the Maratha Navy and Battleships (1973), historian BK Apte writes, “The Siddi was a very dangerous enemy… to prevent his depredations on water and to starve him out, a navy was essential.”

In 1659, Chattrapati Shivaji laid the foundation for the Maratha navy. As documented in the Goa archives by the Portuguese governor general at the time, “A son of Shahaji (father of Chhatrapati Shivaji), the rebel nobleman of the Adilshahi court has captured the territory around Chaul and Bassein (present day Vasai) and has become quite powerful. He has built some men-of-war in Bhimdi, Kalyan and Panvel, ports in Bassein Taluka.”

Chattrapati Shivaji’s ship building exploits threatened the naval superiority of the Portuguese, much to their disdain. They claimed that the Indian Ocean belonged to them since the Pope had granted them the right to appropriate the territories they ‘discovered.’ As Konkan historian AB Rajeshirke writes in Political and Economic Relations between the Portuguese and the Marathas (1981), “The Portuguese could not swallow the very idea that a native power should turn out a naval power thereby threatening the very source of their power.”

The East India Company (EIC) too were wary of the Marathas, fearing that Chattrapati Shivaji’s naval fleet would threaten their dominance of Bombay. This in turn created a series of makeshift alliances between the Siddis, British and Portuguese. “The Siddi became notorious as they would join any anti-Maratha alliance to stay in contention,” writes historian Amarendra Kumar in Kegwin’s Bombay (2014). First, they allied with the Portuguese, then the English in Bombay and lastly with Mughal emperor Aurangzeb. However, their efforts were repeatedly thwarted, first by Chattrapati Shivaji and then by Sambhaji. The latter owes much of this success to one man – Kanhoji Angre.

Born in 1669, Angre was the son of a respected seafarer and as a teen, joined the Maratha navy and became responsible for the strategically important island of Khanderi, just 20 kilometres south of Bombay. In the years to come, the fortress of Khanderi (also known as Colaba), became the home and headquarters of successive generations of the Angres.

According to Apte, Angre’s control of Khanderi worried all the major powers in the region. In an interview with indianexpress.com, Delhi University professor Anirudh Deshpande states that “the Konkan coast was a very lucrative area in terms of international and Indian trade, and almost every power operating on the western coast wanted to take it.” Apte adds that Angre regularly had to compete with these different factions, and “throughout his career, scarcely a season, or a month passed without some naval engagement.”

On two occasions, the English attempted to defeat the Maratha navy. The Portuguese, who described him as a pirate, attempted to have Angre assassinated in 1720. The two even joined forces in an attempt to capture Khanderi. None succeeded. However, Angre died in 1739, and within 30 years of his death, the Maratha’s naval superiority had ended. However, his legacy of fending off every challenger allowed the Marathas to remain competitive in the region, later contributing to their success against the Portuguese and the British.

The Portuguese and the Marathas (Salsette Island)

Back when Bombay was an archipelago of islands, it was bordered on its north by the Salsette group of islands including what is now Bandra, Juhu, Versova and Dharavi. Salsette Island is bordered to the north by Vasai Creek, to the northeast by the Ulhas River, to the east by Thane Creek and Bombay Harbour, and to the south and west by the Arabian Sea. The original seven islands of Bombay, which were joined through land reclamation in the 19th and early 20th centuries to create the city of Mumbai, now form a southward-extending peninsula of the larger Salsette Island.

Salsette was important to the Portuguese as it constituted 1 per cent of the Northern Province, the Portuguese territory that stretched from Daman to Chaul on the Konkan coast. A port in Bassein (Vasai) harboured some of the largest ships in the Portuguese navy, and was a source of major trade. Salsette was so significant that the Portuguese didn’t feel the need to develop Bombay, even ceding the seven islands to the British as part of a dowry in 1661.

The Portuguese had controlled Salsette since 1534 after securing the islands in a treaty with the Muzaffarid dynasty of Gujarat. During their rule over the region, the Portuguese faced constant challenges from adversaries such as the Gujarat Sultanate, the Mughals, the Marathas, the British, and other local and global powers.

To counter these threats, they developed robust defence systems, including forts, watchtowers, bastions, and outposts, many of which still stand today, albeit in a state of neglect. Additionally, the Portuguese strengthened existing forts like Mahim, Karnala, and Belapur after gaining control of the area. These interconnected fortifications were instrumental in repelling attacks from rival powers, allowing the Portuguese to maintain control over the region for more than a century.

As the Marathas under the Peshwas of Pune began to consolidate their power in the early 18th century, they found themselves encircled by rival states, forcing them to adopt an assertive stance toward neighbouring territories. The Portuguese, who governed the strategically vital Province of the North, including Salsette Island, grew increasingly anxious about the security of their holdings.

Under the leadership of Peshwa Bajirao I, the Marathas launched a calculated campaign targeting the Portuguese on the pretext of demanding the customary tribute — one-tenth of revenue or production. However, Bajirao’s ambitions extended far beyond fiscal claims. Salsette, with its prominent coastal ports, represented a critical gateway to the lucrative maritime trade along the Malabar Coast, making it an irresistible prize.

The Marathas’ initial incursions into the Province of the North began with an attack in 1724, followed by a more aggressive assault in 1730. During the latter campaign, the Portuguese came perilously close to losing Salsette, but the timely intervention of the British from the Bombay Islands mediated a temporary peace, allowing the Portuguese to hold onto their territory, for the moment.

By April 1737, the Marathas had escalated their efforts, successfully seizing control of Thane. Yet, they understood that their victory would be hollow without securing other strategic strongholds on Salsette, including the well-fortified Portuguese outposts at Versova, Bandra, and Trombay. At the time, Salsette Island, or Sashti, was home to 157 villages, its landscapes dotted with Portuguese bastions defending these key locations.

The Marathas launched three unsuccessful attempts to capture these fortifications that year. But in their fourth assault, led by Bajirao’s younger brother, Chimaji Appa, they turned the tide. In 1737, the Marathas decisively captured the formidable Bassein Fort (Vasai), which marked the beginning of the end for Portuguese dominance in the region. Over the next two years, the Marathas tightened their grip, capturing Versova and Madh in 1739.

This dramatic campaign reshaped the region’s political landscape. The Marathas consolidated their position by constructing new forts and bolstering existing ones, creating a defensive network that interwove structures from earlier dynasties with those of the Portuguese and, later, the British. The conquest of Salsette and the Province of the North not only cemented Maratha dominance in the area but also set the stage for the rise of Bombay as a pivotal centre of commerce and power.

The Marathas held onto the Salsette islands until 1774, when they lost it to the British during the first Anglo-Maratha war.

The British and the Marathas

Despite a complex and often fraught relationship, the British in Bombay, for strategic reasons, did not obstruct aid to the besieged Portuguese during their conflicts with the Marathas. This dynamic is evidenced in a December 1738 letter from John Pereira Pinto, Commandant of Bassein and Provisional Governor of the Province of the North, to the Governor of Bombay and his council. Pinto noted that British vessels stationed in Bombay regularly supplied provisions and ammunition to the Portuguese-held island of Versova.

However, British neutrality was superficial. While supporting the Portuguese, they were also accused of aiding the Marathas, particularly in their efforts to construct naval ships on Versova Island. According to the records of journalist George William Forrest, Pinto himself urged the British authorities to curb Maratha shipbuilding, suspecting tacit British support for the Maratha project.

The Marathas’ victory over the Portuguese in the Province of the North made them neighbours to another European power — the East India Company. The Company, initially focused on trade, had established itself in Surat under Mughal protection. But the rise of the Marathas under Shivaji altered the balance, as the Marathas’ incursions into Mughal territories diminished Surat’s appeal to European traders. The British sought a more secure base and eventually gained control of Bombay through the marriage treaty of 1661 between England and Portugal.

The British regarded Bajirao I’s military exploits with a mix of respect and trepidation. During the Maratha-Portuguese war, they carefully balanced their actions to avoid antagonising either side, recognising the importance of maintaining Bombay’s safety. Despite strained relations with the Portuguese, the British had no desire to have the militarily assertive Marathas as immediate neighbours.

James Campbell’s Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency (1882) notes that European deserters significantly aided the Maratha forces during this period, bringing expertise in artillery and siege warfare that contributed to their success.

The Portuguese defeat in 1739 profoundly altered the north Konkan’s landscape. With the Marathas now dominant, the British sought to secure their trade privileges and ensure their position in Bombay. They acted as mediators in the 1740 treaty between the Marathas and Portuguese, maintaining a precarious peace while fortifying their foothold in the region.

Even as they negotiated peace, the British eyed Salsette and Vasai for their strategic and economic value. These territories offered fertile land, revenue opportunities, and proximity to Bombay. According to historians GT Gense and BP Banaji, writing in History of the Bombay Presidency (1934), in 1759, 1767, and 1772, British envoys, including Sir Thomas Mostyn, petitioned the Peshwas to cede these lands, but their requests were denied. Instead, Peshwa Madhavrao I bolstered defences in Thane, underscoring the Marathas’ determination to retain control.

The tide turned with internal strife in the Maratha Confederacy. The civil war between Raghunathrao and Nana Phadnavis’s faction weakened Maratha defences, providing the British with an opportunity. In December 1774, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Keating led a military campaign against Salsette. After multiple assaults, the British captured key forts, including Versova, Thane, and Karanja, within a week. The campaign marked the beginning of British dominance in north Konkan, sending shockwaves through both Maratha and Portuguese camps.

When the East India Company took control of Salsette Island in the late 18th century, they inherited a landscape of desolation. The once-flourishing Portuguese stronghold, dotted with grand churches, chapels, and estates, had fallen into profound neglect. Dr Karol Hove, a Polish traveller who visited the island in 1787, captured its dilapidated state in vivid detail in his diary.

“On both sides of the road, wherever I cast my eyes,” he observed, “I saw many remains of churches and chapels, which were surrounded by large buildings; but all pining in decay. I judged by this ruinous appearance, this island has been in the time of the Portuguese in a flourishing state; at present, however, it is entirely deserted from human notice.”

Rehabilitation and development became an immediate priority for the British. Historian N Benjamin, in the journal Settlement of Salsette Island (2004), notes that the Company faced the dual challenges of revitalising the island’s economy and re-establishing human habitation.

Recognising the potential of Salsette’s fertile yet underutilised lands, the Company sought to attract settlers who could cultivate and manage the area. An East India Company commander wrote to the Bombay Government, stating, “as so large a part of Salsette is uncultivated, we recommend to you to give every suitable encouragement to the Parsees to settle there, who we understand are a very industrious and quiet people,” (as cited in Forrest’s Bombay Gazette, 1887). This policy led to the appointment of Kavasji Rustomji, a Parsi leader, as the village head of several key villages. Under his stewardship, Salsette began to revive.

Rustomji played a pivotal role in fostering a Parsi migration to Thane, the island’s principal city. His efforts extended beyond administration; he contributed to the spiritual and cultural life of the community by building a Tower of Silence and a fire temple, further anchoring the Parsi presence on Salsette.

The British strategy of encouraging industrious settlers like the Parsis not only rehabilitated Salsette but also laid the groundwork for its integration into the rapidly urbanising Bombay Presidency. What had been a forgotten remnant of Portuguese ambition became a vital part of the region’s economic and cultural tapestry.

The Maratha Confederacy’s defeat at the Battle of Panipat in 1761 and subsequent internal conflicts left the newly acquired north Konkan territories vulnerable. By 1785, Salsette and Vasai were formally ceded to the British. The British settlement in Bombay flourished under stable administration, attracting trade, industry, and population growth.

As the Marathas expanded their influence elsewhere, the British consolidated power in the western coastal strip, transforming Bombay from a modest trading post into a burgeoning colonial metropolis.

The Marathas’ legacy in Bombay is one of profound yet understated influence, a testament to their ambition, resilience, and strategic foresight. While the British ultimately emerged as the architects of modern Bombay, the Marathas’ campaigns in Salsette, their triumph over the Portuguese, and their attempts to assert control over the islands reflect their vital role in shaping the region’s early modern history. For the Marathas, Bombay was not merely a cluster of islands but a gateway to maritime power, economic prosperity, and regional dominance — a vision that outlasted their political hold.

(Next in the series – the history of Maratha indentured labourers in Mauritius)